The Full Moon, photographed in July 2016 from Melbourne, Florida. Credit: Michael Seeley/Flickr.

The phenomenon of a Full Moon arises when our planet, Earth, is precisely sandwiched between the Sun and the Moon. This alignment ensures the entire side of the Moon that faces us gleams under sunlight. Thanks to the Moon’s orbit around Earth, the angle of sunlight hitting the lunar surface and being reflected back to our planet changes. That creates different lunar phases.

The next Full Moon in 2024 is at 6:17 a.m. on Sunday, July 21, and is called the Buck Moon.

We’ll update this article multiple times each week with the latest moonrise, moonset, Full Moon schedule, and some of what you can see in the sky each week.

Here’s the complete list of Full Moons this year and their traditional names.

2024 Full Moon schedule and names of each

(all times Eastern)

- Jan. 25 — 12:54 p.m. — Wolf Moon

- Feb. 24 —7:30 a.m. — Snow Moon

- March 25 — 3 a.m. — Worm Moon

- April 23 — 7:49 p.m. — Pink Moon

- May 23 — 9:53 a.m. — Flower Moon

- Friday, June 21 — 9:08 p.m. — Strawberry Moon

- Sunday, July 21 — 6:17 a.m. — Buck Moon

- Monday, Aug. 19 — 2:26 p.m. — Sturgeon Moon

- Tuesday, Sept. 17 — 10:34 p.m. — Corn Moon

- Thursday, Oct. 17 — 7:26 a.m. — Hunter’s Moon

- Friday, Nov. 15 — 4:28 p.m. — Beaver Moon

- Sunday, Dec. 15 — 4:02 a.m. — Cold Moon

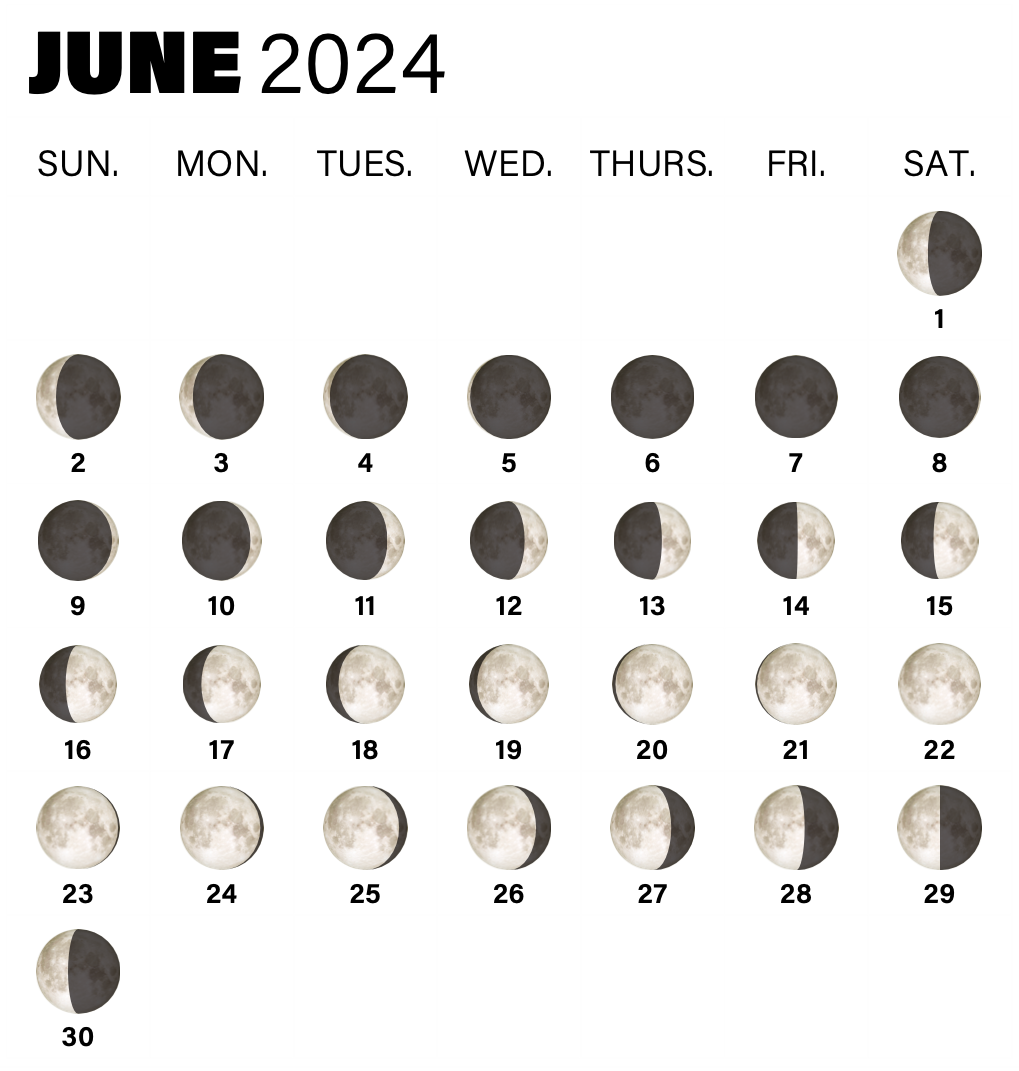

The phases of the Moon in June 2024

The images below show the day-by-day phases of the Moon In June. The Full Moon in June was at 6:17 a.m. on Friday, June 21.

The moonrise and moonset schedule this week

The following is adapted from Alison Klesman’s The Sky This Week article, which you can find here.

*Times for sunrise, sunset, moonrise, and moonset are given in local time from 40° N 90° W. The Moon’s illumination is given at 12 P.M. local time from the same location.

Friday, June 28

The Moon passes 0.3° north of Neptune at 5 A.M. EDT. Roughly half a day later, at 5:53 P.M. EDT, the Moon reaches Last Quarter as it slowly wanes from Full to New.

Sunrise: 5:34 A.M.

Sunset: 8:33 P.M.

Moonrise: 12:34 A.M.

Moonset: 12:56 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waning gibbous (52%)

Saturday, June 29

Mercury passes 5° due south of the bright star Pollux in Gemini at 6 A.M. EDT. You can catch the pair in the evening sky just after sunset, though you’ll need to be quick — 40 minutes after sunset, Mercury is just 4.5° high, while Pollux is just starting to pop out against the darkening sky to the planet’s upper right.

Mercury is a bright magnitude –0.8, compared with Pollux at magnitude 1.2. To the right of Pollux, if you’re particularly sharp-eyed, you might also spot magnitude 1.6 Castor, Gemini’s alpha star (although it is brighter, Pollux is cataloged as Beta [β] Geminorum).

Through a telescope, Mercury’s disk shows off its gibbous phase, some 80 percent illuminated. If you watch it over the next few days, you’ll notice it waning night by night. The solar system’s smallest planet has an apparent diameter tonight of 6″, which will slowly grow even as its phase wanes in the coming days.

Sunrise: 5:35 A.M.

Sunset: 8:33 P.M.

Moonrise: 12:58 A.M.

Moonset: 2:08 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waning crescent (41%)

Sunday, June 30

Sunrise: 5:35 A.M.

Sunset: 8:33 P.M.

Moonrise: 1:23 A.M.

Moonset: 3:21 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waning crescent (30%)

Monday, July 1

The Moon now passes 4° north of Mars at 2 P.M. EDT. Visible early this morning, the pair stands 30° high in the east an hour before sunrise, with the Moon appearing directly above magnitude 1 Mars. They are both in the constellation Aries, whose brightest star is a full magnitude fainter than Mars: magnitude 1 Hamal, which sits farther above the Moon.

Even higher in the sky, above Aries, is the constellation Andromeda. Earlier in the morning — say, two or three hours before sunrise — you might try to spot the Milky Way’s largest neighbor, the Andromeda Galaxy (M31). Glowing at magnitude 3.4, Andromeda is visible to the naked eye under clear, dark conditions. It’s located 1.3° west of magnitude 4.5 Nu (ν) Andromedae, making it relatively easy to find.

Lying just 2.5 million light-years away, Andromeda stretches a full 3° on the sky. Take your time enjoying it with any-sized telescope; larger apertures will show more detail, such as a brighter central core and wispy spiral arms. You may also spot its two brightest satellite galaxies, M32 and NGC 205, just ½° south and northwest of the galaxy’s center, respectively,

Sunrise: 5:35 A.M.

Sunset: 8:32 P.M.

Moonrise: 1:51 A.M.

Moonset: 4:35 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waning crescent (20%)

Tuesday, July 2

Continuing along the morning line of planets, the Moon passes 4° north of Uranus at 6 A.M. EDT. You can use our satellite to help you find the distant ice giant in the pre-dawn sky; an hour before sunrise, pull out your binoculars or any small scope and drop those 4° south of the Moon to land on Uranus, the penultimate planet from the Sun. Glowing at 6th magnitude, Uranus’ disk spans just 3″, thanks to its distance. It should appear as a “flat,” disklike star compared to the pinprick background stars around it.

Sunrise: 5:36 A.M.

Sunset: 8:32 P.M.

Moonrise: 2:24 A.M.

Moonset: 5:50 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waning crescent (12%)

Wednesday, July 3

The Moon passes 5° north of Jupiter at 4 A.M. EDT. An hour before local sunrise, the planet is some 12° high in the east, standing above and just to the left of Aldebaran, the red giant star that marks the eye of Taurus the Bull. Jupiter remains a bright magnitude –2, making it easy to pick out in the early-morning sky even as dawn begins to approach. While you’re observing the region, test how long you can continue to see the Pleiades star cluster to Jupiter’s upper right; this gaggle of young stars is one of the most famous open clusters in our sky.

Meanwhile, the Moon itself may actually be a bit difficult to spot, as the thin waning crescent shows off only the slightest sliver of the western limb. With a telescope, see if you can identify the dark, round patch of the crater Grimaldi near the southwestern edge of our satellite. This feature is well known for its broad, dark, flat floor and is not technically a crater, but more of a basin where there is greater than average mass just beneath the surface.

In addition to the finer features on the Moon’s surface, see if there’s any earthshine today. Visible with the naked eye, this phenomenon casts the portion of the lunar surface in Earth’s shadow in a soft, gray light — this is reflected sunlight bouncing off Earth and illuminating the Moon.

Sunrise: 5:37 A.M.

Sunset: 8:32 P.M.

Moonrise: 3:04 A.M.

Moonset: 7:00 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waning crescent (6%)

Thursday, July 4

Sunrise: 5:37 A.M.

Sunset: 8:32 P.M.

Moonrise: 3:53 A.M.

Moonset: 8:03 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waning crescent (2%)

Friday, July 5

Earth reaches aphelion, the farthest point in our nearly (but not-quite) circular orbit around the Sun, at 1 A.M. EDT. At that time, our planet will sit 94.5 million miles (151 million kilometers) from the Sun.

New Moon occurs this evening at 6:57 P.M. EDT, ensuring dark skies for those seeking to observe the dwarf planet 1 Ceres at opposition, a point it reaches tonight at 8 P.M. EDT.

Sunrise: 5:38 A.M.

Sunset: 8:32 P.M.

Moonrise: 4:51 A.M.

Moonset: 8:56 P.M.

Moon Phase: New

The phases of the Moon

The phases of the Moon are: New Moon, waxing crescent, First Quarter, waxing gibbous, Full Moon, waning gibbous, Last Quarter, and waning crescent. A cycle starting from one Full Moon to its next counterpart, termed the synodic month or lunar month, lasts about 29.5 days.

Though a Full Moon only occurs during the exact moment when Earth, Moon, and Sun form a perfect alignment, to our eyes, the Moon seems Full for around three days.

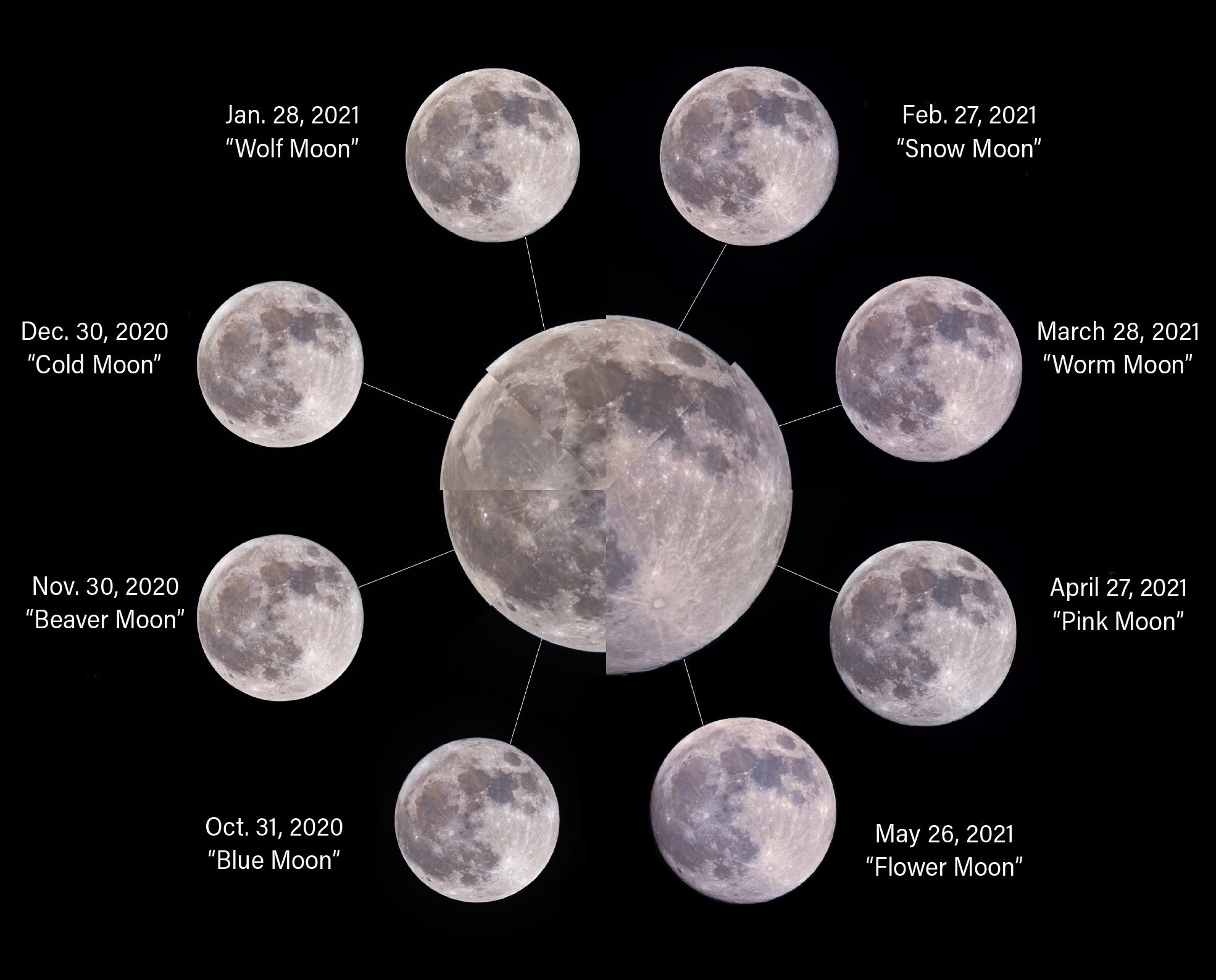

Different names for different types of Full Moon

There are a wide variety of specialized names used to identify distinct types or timings of Full Moons. These names primarily trace back to a blend of cultural, agricultural, and natural observations about the Moon, aimed at allowing humans to not only predict seasonal changes, but also track the passage of time.

For instance, almost every month’s Full Moon boasts a name sourced from Native American, Colonial American, or other North American traditions, with their titles mirroring seasonal shifts and nature’s events.

Wolf Moon (January): Inspired by the cries of hungry wolves.

Snow Moon (February): A nod to the month’s often heavy snowfall.

Worm Moon (March): Named after the earthworms that signal thawing grounds.

Pink Moon (April): In honor of the blossoming pink wildflowers.

Flower Moon (May): Celebrating the bloom of flowers.

Strawberry Moon (June): Marks the prime strawberry harvest season.

Buck Moon (July): Recognizing the new antlers on bucks.

Sturgeon Moon (August): Named after the abundant sturgeon fish.

Corn Moon (September): Signifying the corn harvesting period.

Hunter’s Moon (October): Commemorating the hunting season preceding winter.

Beaver Moon (November): Reflects the time when beavers are busy building their winter dams.

Cold Moon (December): Evocative of winter’s chill.

In addition, there are a few additional names for Full Moons that commonly make their way into public conversations and news.

Super Moon: This term is reserved for a Full Moon that aligns with the lunar perigee, which is the Moon’s nearest point to Earth in its orbit. This proximity renders the Full Moon unusually large and luminous. For a Full Moon to earn the Super Moon tag, it should be within approximately 90 percent of its closest distance to Earth.

Blue Moon: A Blue Moon is the second Full Moon in a month that experiences two Full Moons. This phenomenon graces our skies roughly every 2.7 years. Though the term suggests a color, Blue Moons aren’t truly blue. Very occasionally, atmospheric conditions such as recent volcanic eruptions might lend the Moon a slightly blueish tint, but this hue isn’t tied to the term.

Harvest Moon: Occurring closest to the autumnal equinox, typically in September, the Harvest Moon is often renowned for a distinct orange tint it might display. This Full Moon rises close to sunset and sets near sunrise, providing extended hours of bright moonlight. Historically, this was invaluable to farmers gathering their produce.

Common questions about Full Moons

What is the difference between a Full Moon and a New Moon? A Full Moon is witnessed when Earth is between the Sun and the Moon, making the entire Moon’s face visible. Conversely, during a New Moon, the Moon lies between Earth and the Sun, shrouding its Earth-facing side in darkness.

How does the Full Moon influence tides? The Moon’s gravitational tug causes Earth’s waters to bulge, birthing tides. During both Full and New Moons, the Sun, Earth, and Moon are in alignment, generating “spring tides.” These tides can swing exceptionally high or low due to the combined gravitational influences of the Sun and Moon.

Here are the dates for all the lunar phases in 2024:

| New | First Quarter | Full | Last Quarter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jan. 3 | |||

| Jan. 11 | Jan. 17 | Jan. 25 | Feb. 2 |

| Feb. 9 | Feb. 16 | Feb. 24 | March 3 |

| March 10 | March 17 | March 25 | April 1 |

| April 8 | April 15 | April 23 | May 1 |

| May 7 | May 15 | May 23 | May 30 |

| June 6 | June 14 | June 21 | June 28 |

| July 5 | July 13 | July 21 | July 27 |

| Aug. 4 | Aug. 12 | Aug. 19 | Aug 26 |

| Sept. 2 | Sept. 11 | Sept. 17 | Sept. 24 |

| Oct. 2 | Oct. 10 | Oct. 17 | Oct. 24 |

| Nov. 1 | Nov. 9 | Nov. 15 | Nov. 22 |

| Dec. 1 | Dec. 8 | Dec. 15 | Dec. 22 |

| Dec. 30 |