This story previously aired on June 9, 2018. It was updated on July 6, 2024.

Produced by Lourdes Aguiar and Cindy Cesare

Every morning for the last 37 years, Jim Alt wakes up terrified — thinking that it’s 1978, and that he’s just been brutally attacked on Torrey Pines State Beach.

“When I become aware that I’m awake, I do not open my eyes. I put my hands on the bed, and I feel for that sheet or I feel for sand of a beach,” said Alt.

“You still do that?” “48 Hours” correspondent Richard Schlesinger asked.

“Yes, sir,” Alt replied. “Before my eyes are open I want to know where I’m at.”

It wasn’t always this way. The beach used to be Alt’s second home — a safe place, a fun place.

“You were a big surfer,” Schlesinger noted.

“Absolutely,” Alt said. “There’s not a feeling on earth like surfing. It’s just — there’s a big rush inside your body.”

Rick Selga has felt that rush. He was one of Alt’s good friends back then.

“Who was the better surfer between the two of you?” Schlesinger asked Selga.

“Uh, probably he was,” he replied with a laugh.

“Do you remember what he was like back then?” Schlesinger asked of Alt.

“He was a big, strong, funny, happy guy. He was probably the guy that everybody looked up to,” Selga replied.

And this is probably one reason why: Alt was featured in a wet suit ad in Surfer Magazine.

“We were rock stars, all of us in there,” Alt recalled. “… when that magazine — that issue — came out, we autographed quite a few.”

“And he had a lot of girls that liked him. But he didn’t see anybody else but her,” said Selga.

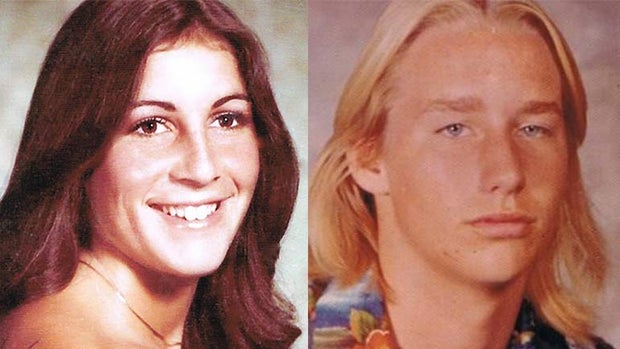

Jim Alt only had eyes for 15-year-old Barbara Nantais. They were the all-American couple. Jim, the surfer, had been dating Barbara, the cheerleader, for nine months.

“Man, just a beautiful girl — brown hair, brown eyes,” Alt said fondly. “I was in love with her the minute I saw her.”

They were introduced by Barbara’s sister, Sue Nantais.

“She was outspoken … Really stubborn, and set in her ways,” Sue Nantais said of her sister. “We had lots of arguments [laughs] and fights and disagreements as sisters do.”

Barbara’s parents, Ralph and Judy Nantais, knew they had their work cut out for them pretty early on.

“So she wasn’t just another pretty face,” Schlesinger commented.

“No, she wasn’t,” Ralph Nantais laughed, “she was tough as nails.”

“She was a popular, defiant, beautiful, pain in the ass, wonderful daughter. You know?” Judy Nantais said. “God gave her to me to keep me humble, and it worked.”

On the weekend of Aug. 12, 1978, Ralph and Judy Nantais left town to visit friends. A family friend was looking after Barbara and her three siblings. Before leaving, Ralph Nantais took Jim Alt aside.

“What did you tell him?” Schlesinger asked.

“Take care of my girl, OK? And make sure that she’s safe,” said Ralph Nantais.

“I told her father and mother, you know, that we would stay put. And again, that — that, you know, I’ve said it before, it’s the biggest mistake or the biggest lie I’ve ever told in my life,” Alt told Schlesinger.

Almost as soon as Barbara’s parents left, she and Alt hopped into a station wagon with Rick Selga and his girlfriend. They all drove off to the beach.

“I remember as they pulled off though, just saying, ‘You guys better be careful.’ And they’re kinda like, ‘Yeah, haha,'” Sue Nantais said. “My sister was like, ‘See ya!'”

The four friends eventually ended up at Torrey Pines Beach.

“The parking lot was filled with people. It was like a big party,” said Selga.

Around 9:30 p.m., the friends called it a night. Selga and his girlfriend decided to sleep in the station wagon and Alt and Barbara went down to the beach for some privacy.

“We zip the sleeping bags together, and crawled in them and went to sleep. She was in my arms. That’s the last thing I remember,” said Alt.

The next morning, Alt woke up cold and alone and wet — he was covered in blood.

“I’m freezing. I’m — I’m feeling for Barbara, don’t know where she is. I don’t know anything. I can’t see anything, don’t hear anything,” he said.

Blinded and disoriented, Alt had to feel his way along a fence up the sandy hill to the parking lot where his friends were sleeping in the car.

“And Jim came up here, and he — he was down low like this, and he rapped on the window,” Selga demonstrated, kneeling in the beach parking lot.

“And what did he look like then?” Schlesinger asked.

“His face was swollen. Blood, all over his blonde hair,” said Selga.

Jim Alt had been savagely beaten with a rock and a log from a fire pit on the beach

“Did he say anything to you?” Schlesinger asked Selga.

“He goes, ‘Go find Barb,'” he replied. “So I ran down to the beach lookin’ for her. … And she was there.”

Barbara’s nude lifeless body lay on the beach.

“I was thinking … ‘What do I do?'” Selga recalled. “I think that I just yelled at some people to call the police.”

News report: Homicide officers say what started out as an evening with friends turned out to be a night of death.

CBS News

Paul Ybarrondo was a Sergeant for the San Diego Police Department. He was one of the first investigators on the scene.

“When we uncovered the body, it was — covered with sand,” Ybarrondo told Schlesinger as they walked along the beach where Barbara’s body was found. “She had some very severe-looking wounds on her head. Looked like she had probably been struck with something, perhaps the rocks that were found nearby.”

Barbara’s murder had been vicious; there was sand in her mouth and the killer left a gruesome mark.

“It appeared that somebody had taken a sharp instrument and cut around the areola of her breast, and also cut around the nipple of the breast,” said Ybarrondo.

“So she’d been sort of mutilated,” said Schlesinger.

“Mutilated,” Ybarrondo affirmed. “Later on, it was determined she had been raped and sodomized.”

Soon after, Barbara’s parents were notified.

“And I just started screaming, ‘No, no, no!’ I must have said it 50 times,” said Judy Nantais.

“It was like somebody took a sledgehammer and hit me in the head … because we didn’t even know that the kids were down there. We had no idea,” said Ralph Nantais.

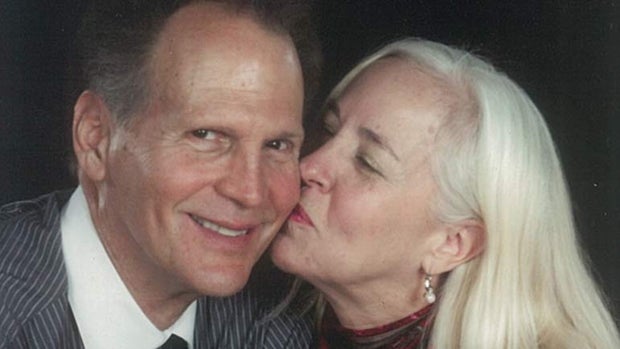

Jim Alt

Jim Alt had been rushed to the hospital. He had suffered traumatic brain injury and was in a coma for days. When he awoke, he had no memory of the attack.

“I’ve got titanium in the cranium, stainless steel. Um, I’ve got that — that plate that runs right about there,” he said, circling the right side of his forehead with a finger.

“This was a serious, life-threatening attack,” Schlesinger noted.

“Yes sir. I almost did not make it,” said Alt.

Alt was briefly investigated, but ruled out as a suspect — his injuries were too severe. Ybarrondo and other investigators tracked down other leads, but the police could not find the killer. The bloody attack and murder haunted everyone for years.

“They were just kids, you know. And … that stuff didn’t happen,” said Selga.

But a few years later, Claire Hough’s body was found on Torrey Pines Beach.

“She was murdered identically to Barbara,” said an emotional Jim Alt.

SERIAL KILLER?

In the years after Barbara Nantais’ murder, her family struggled with the overwhelming loss and pain.

“There were situations where I’d wake up in a cold sweat, crying,” said Ralph Nantais.

“Just the sadness at losing this child that you loved,” Judy Nantais said. “When you’re the mom, you just carry that. … I felt like I — was a complete failure as a mother.”

Barbara’s parents were both sad and angry at their daughter for lying to them, but Ralph Nantais was especially furious at Jim Alt.

“I didn’t want to see him. … I didn’t want to talk to him,” he said. “That’s exactly what I felt. You didn’t keep my little girl safe. I was very, very upset.”

“It hurts,” Jim Alt said with regret “I didn’t bring their daughter home.”

Kim Jamer

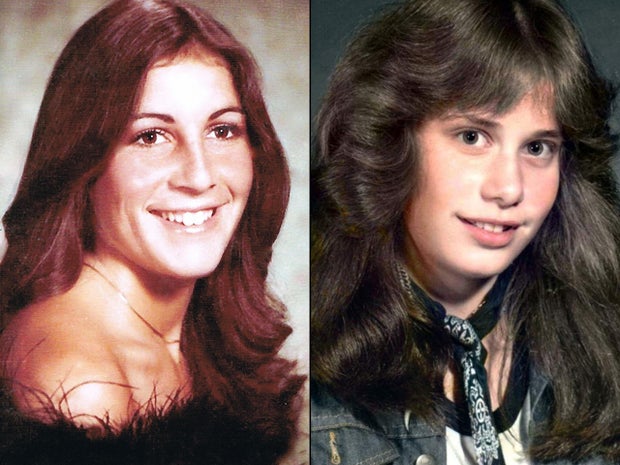

Six years later, Claire Hough’s loved ones faced the same pain that originated in the same place. She was like Barbara Nantais, a year younger — just 14, smart and spirited and she loved the beach.

“She just had an inner light, a joy about her. It’s hard to explain unless you’ve met her,” said Kim Jamer, Claire Hough’s best friend, who described her as “very gentle, funny, kind.”

Claire’s parents, Sam and Penny Hough, were — and are — immensely proud of her.

“She was the class mediator,” Penny Hough said. “Kids who got into arguments would ask Claire to adjudicate.”

“Couple of times she got in trouble in school because the teacher had accused someone wrongly and Claire wouldn’t put up with it. She fought back,” added Sam Hough.

Claire learned to love the ocean early on. She grew up on the coast of Rhode Island and spent as much time as she could walking along the shore with Kim Jamer.

“We grew up looking for treasures and bringing her mom pretty things home from the ocean. Sea glass … and pretty shells,” she recalled.

Claire had also spent a lot of time on San Diego’s beaches. Her grandparents lived just a few blocks away from Torrey Pines Beach. One of the first pictures of Claire was taken there.

Hough family

“She was still small enough to be carried,” Penny Hough said. “This may be the first — her first introduction to real ocean surf.”

The Houghs had always considered it a safe place, and in the summer of 1984, they sent Claire and her brother out to California for a visit with their grandparents. Kim Jamer went along, too.

“We could just be silly and nobody knew us and it didn’t matter how goofy we got,” Jamer said. “And it was just really fun.”

The night before Jamer was supposed to head home, Claire convinced her to sneak out of her grandparents’ house and go to the beach after dark. But once they got there and settled near their favorite spot by the bridge, Jamer almost immediately had a panic attack.

“It was just an awful feeling,” Jamer said. “I knew how freaked out I was … how somebody could just walk right up and by you without you even knowing they were there.”

“You asked Claire to make you a promise, when you were back at the house,” Schlesinger noted. “What was the promise?”

“I just didn’t want her sneaking out by herself again,” Jamer replied.

KFMB

Two days later, after Jamer went back to Rhode Island, Claire broke that promise. On Aug. 24, 1984, Claire Hough’s body was found by a beachcomber near the bridge. Retired detective Paul Ybarrondo also worked on this case and was interviewed by the local CBS station back then.

“We are evaluating all the evidence we recovered at the scene,” Ybarrondo told a reporter.

Claire had been found just a few hundred yards from where Barbara Nantais had been killed.

“To me it was — a lot of similarities there,” Ybarrondo told Schlesinger.

Like Barbara Nantais, Claire Hough also had been beaten, strangled, and sexually assaulted.

“It was determined at the autopsy that this girl had a lot of sand packed in her mouth and larynx area. Our other victim had sand in her mouth,” Ybarrondo explained.

But perhaps most chilling, like Barbara’s, Claire’s breast had also been mutilated.

“We either have — serial killer or a repeat performance by the person that probably did the first case,” said Ybarrondo.

It didn’t take long to find a promising suspect. As soon as they heard about their daughter’s death, Sam and Penny Hough went to Torrey Pines State Beach. Before long, they were approached by a man named Wallace Wheeler. He was the beachcomber who had found Claire’s body.

“He said, ‘I’m Wally Wheeler. I’m a psychic,” said San Hough.

“He said what?” Schlesinger asked.

“With his arm outstretched,” Penny Hough said. “‘Hi, I’m Wally Wheeler, I’m a psychic.'”

From there, things only got stranger.

“And then he went on for a half an hour with this long tale about how he could see at night. He had been … a fighter pilot,” Sam Hough continued.

“What did you think of Wally Wheeler, the psychic?” Schlesinger asked.

“He was strange,” said Penny Hough.

“So then we called the police to … tell them that,” said Sam Hough.

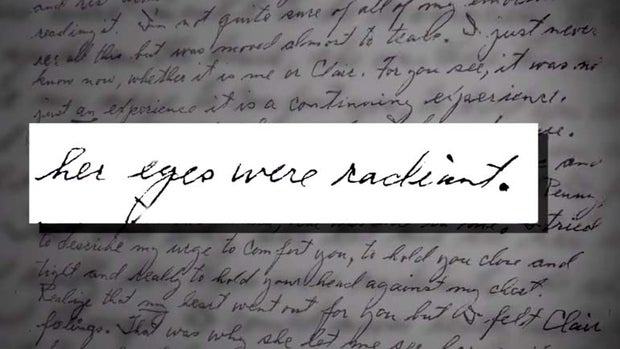

The police encouraged Claire’s parents to keep communicating with Wheeler, thinking he might confess or at least give them some useful information. Wheeler wrote long and rambling letters to the Houghs, one of them saying Claire was coming to him in visions.

“‘That was why she let me see her smiling face and really her eyes were radiant,'” Sam Hough read aloud from the letter. “This is a guy who found a bloody, mutilated body and he’s talking about a smiling face and radiant eyes.”

The letters were very odd. The police questioned Wheeler, but he never confessed to anything. The letters eventually stopped.

“What was the last thing that you heard about Wallace Wheeler?” Schlesinger asked.

“That he had killed himself,” Penny Hough replied.

“He threw himself off the top of a building — a 13-story building and died,” added Sam Hough.

Investigators would later tell the Houghs they had ruled Wheeler out as a suspect, but they were convinced for years that he was their daughter’s killer.

“You thought he was involved somehow?” Schlesinger asked

“Oh yeah,” Sam Hough replied. “We assumed that Wheeler … that he had done it.”

For all the intrigue surrounding Wallace Wheeler, the loved ones of the first victim, Barbara Nantais, had never even heard of him at the time. In fact, the families did not even know about each other. But around 2008, the San Diego Police Department posted the cases on their website and for the first time said publicly that they believed Claire Hough and Barbara Nantais had likely been murdered by the same killer.

“I was mad that it happened to Claire and we weren’t informed,” said an emotional Sue Nantais.

But who may have been responsible would remain a mystery for four more years until advanced DNA testing revealed two suspects — and one of them was one of their own.

A BREAK IN THE COLD CASE

For decades after the murders of Barbara Nantais and Claire Hough, the San Diego Police Department kept investigating sporadically. But nothing had ever materialized. Claire’s friend, Kim Jamer, kept waiting for some news.

“Do you think about this case a lot?” Schlesinger asked Jamer.

“All the time,” she replied. “I mean, you know, nothing’s going to bring your friend back. And you just hope that no one is out there hurting other people.”

In 2012, there was finally a promising development. The cases were reopened, and investigators were hoping advanced DNA technology would change the course of things. It was encouraging for Barbara’s parents, Judy and Ralph Nantais.

“I was cautiously optimistic …”said Judy Nantais.

They would be disappointed. The new DNA tests would find nothing useful on their daughter, but Claire Hough’s friend, Kim Jamer, would soon get a visit from a detective.

“He brought several pictures,” she said. “‘Did you see any of these people during your trip?’ I didn’t recognize anything.”

Jamer was given few details, but she had a feeling that investigators were finally onto something.

“I was like, ‘Finally … Somebody’s really looking into this,'” she said.

U-T San Diego/ZUMA Wire; Rebecca Brown

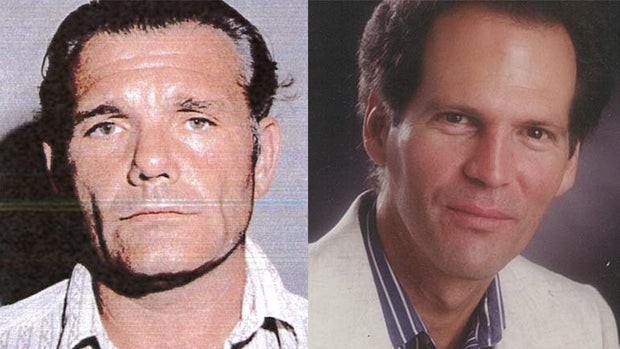

“48 Hours” obtained the San Diego Police Department case affidavits and search warrants. Here’s what Kim Jamer didn’t know. The police had found two DNA hits on Claire Hough. Blood on her jeans was linked to a convicted rapist named Ronald Tatro. The other DNA — a tiny, microscopic amount reportedly found inside Claire — was linked to a man named Kevin Brown. Police knew him; he was a former criminalist in their lab.

Rebecca Brown, a Catholic school teacher, had been married to 61-year-old Kevin Brown for more than 20 years. Kevin Brown retired from the San Diego Police Department in 2002.

“I was getting ready for work. And there was the knock. And two detectives were there,” said Rebecca Brown.

“So I thought, OK, they’re talking about some case that he worked on,” she continued.

The couple met in 1992 through the old-school version of online dating: the classifieds. A few months later, they married.

“He was so sweet,” Rebecca Brown said. “… he would open the car door for me. And he loved animals like I did. He loved cats. … he was a sweetheart.”

The Browns had led a quiet life revolving around church, travel, and their pets before that visit by investigators in January 2014.

“Did you listen to what they were saying to him?” Schlesinger asked.

“I started. And I thought, ‘Well, that’s kinda going odd. What’s with this?'” Rebecca Brown replied.

The detectives showed Kevin Brown a picture of Ronald Tatro, and asked if he knew him.

“What did he say?” Schlesinger asked journalist James Vlahos.

“He said, ‘I’ve never seen this man. I don’t know him,'” he replied.

James Vlahos, a CBS News consultant, wrote about the case in October 2015 for The Atlantic Magazine.

“Did the police go and talk to Ronald Tatro when they found his DNA in Claire Hough’s body?” Schlesinger asked.

“They would have liked to have done that but … Ronald Tatro was already dead.” Vlahos replied.

Tatro had drowned in what was ruled a boating accident in Tennessee in 2011. To this day, there is suspicion it was a suicide.

“His wallet had been placed on the seat … his glasses had been placed on the seat. And they said it looked as if he intended to go into the water, instead of having fallen in by accident,” Vlahos said. “… and another thing that certainly raises eyebrows is that his death took place on the anniversary of Claire Hough’s murder.”

Kevin Brown, the retired criminalist, was now the only living suspect. Police showed him a picture of Claire Hough.

“And when they showed him a picture of Claire Hough what did he say? Schlesinger asked Vlahos.

“‘Oh, sure, I remember her,'” he replied.

The detectives told Brown that his DNA had been found in the evidence.

“They didn’t tell him where or how they found it. And the police maintained that it was Kevin who first mentioned the possibility of it being found on a vaginal swab,” said Vlahos.

The investigation ramped up quickly. That same afternoon, investigators served a search warrant on his property, looking for any evidence related to the murders of both Claire Hough and Barbara Nantais because they were so similar.

“I said, ‘you’ve gotta … clear this up. This is crazy,” Rebecca Brown said. “And he said, ‘I tried telling them I don’t know what they’re talking about. … I never killed anybody in my life. You know that.’ And I do know that. In my deep core, I know he never killed anybody.”

But investigators believed Kevin Brown had a dark side. At the time of Claire Hough’s murder, Kevin Brown was a bachelor in his 30s and had a randy reputation at the crime lab.

Retired criminalists Jim Stam and John Durina worked with Kevin Brown in the lab for years.

“He had a nickname, Kinky Kevin Brown. That was because we knew that he frequented strip clubs,” said Stam.

“They called him Kinky Kevin?” Schlesinger asked.

“Yeah … his nickname was Kinky. Yeah,” Stam replied.

“Did he brag about going to the strip clubs? Did he make any secret of it?” Schlesinger asked.

“Early on, I don’t think he kept it a secret,” Stam said. “But he did have friends that would go with him … to either a movie or a strip club, I believe.”

“He would go to, what? Dirty movies?” Schlesinger pressed.

“I believe it was a porn movie, yes,” said Durina.

Durina and Stam never saw any inappropriate behavior by Brown in the lab, but he made some female colleagues uncomfortable.

“There was a criminalist who worked with Kevin Brown … and she describes how Kevin took a report of a violent rape … and when she was alone in a lab with him, read it aloud to her and made a remark along the lines of, ‘Isn’t that funny?'” Vlahos explained. “After that she never felt comfortable being alone with him in the lab again.”

As they dug into Kevin Brown’s background, investigators learned more about his hobbies. He enjoyed photography, and in the 80s, he went to lingerie and boudoir shoots advertised in a local magazine. Photographer Rocky Forguson took photos of aspiring models with Kevin Brown.

“So they pose for the photographer and in return, they get a free picture,” Schlesinger commented to Forguson.

“Yes,” he replied.

But Forguson says that sometimes certain photographers would make arrangements for private sessions that were racier.

“And Kevin did that?” Schlesinger asked.

“Kevin did his own thing,” Forguson explained. “If he likes somebody, he’ll hire his own models.”

“In these private sessions what would happen?” Schlesinger asked.

“Adult type stuff,” said Forguson.

“Adult stuff. Naughty stuff?” Schlesinger asked.

“Yes,” Forguson replied, “explicit photos.”

Kevin Brown’s pastimes as a bachelor may have raised detectives’ eyebrows, but his statements during the investigation made them even more suspicious. Although he initially denied having actually met Claire Hough, Brown later seemed to make a startling admission.

“He had done some thinking and that he now did recall having met someone named Claire in the 1980s and possibly having sex with her,” said Vlahos.

And then he got himself in even deeper trouble. According to the affidavit, Kevin Brown volunteered to take a lie detector test. He failed. After the polygraph, an investigator talked to him about Claire Hough saying, “I don’t believe for a second that you thought she was 14.” Brown reportedly responded “I had no idea.” Then, police learned, Kevin Brown had called a friend.

“And told him, allegedly, ‘The police are looking at me as a suspect. This girl I photographed on the beach ended up dead,'” said Vlahos.

QUESTIONING THE DNA

Ever since investigators got that DNA hit on Claire Hough in 2012, they had been quietly trying to build a case against Kevin Brown. But his wife, Rebecca Brown, stood by him.

“I never ever thought he was a killer. Never. Never,” she said emphatically. “This is a man who didn’t have a mean bone in his body.”

“Well, you know all those things that people are saying about … he was going to strip clubs and taking photographs of naked women,” said Schlesinger.

“He had shown me some. And [the] majority were just, like … just cutesy poses. Glamour shots,” said Rebecca Brown.

“Did the fact that some of those photo shoots went further than others bother you about him?”

“No, he had a normal male sex drive. And that was back when he was single and he would’ve thought ‘Wow, this is great!'” Rebecca Brown replied.

Attorneys Gene Iredale and Gretchen Von Helms represent the Browns.

“If everybody who ever looked at a photo of a scantily clad woman … if everybody who ever went to a strip club … is likely to be a serial killer, I’m afraid we’re going to have to build quite a few more prisons,” said Iredale.

“We do not convict people on their character,” said Von Helms.

Hough and Nantais families

“This was a violent, sadistic, choking killing,” she continued. “The scope of what happened to these poor young women who were brutally sexually assaulted and murdered is quite different from going to a strip club or going into a porn shop or reading an off-color story.”

The lawyers argue that there is almost no case against Kevin Brown. For starters they say, investigators could never say if or when or how Kevin Brown, the mild-mannered criminalist, met Ronald Tatro, the violent convicted rapist.

“Zero evidence that they’d ever seen each other or met at any time. Zero,” said Iredale.

They say there are perfectly innocent explanations for Kevin Brown’s actions and statements, like the one he made when detectives showed him a picture of Claire Hough.

“He said at one point, ‘Oh, I remember her.’ Why did he say that?” Schlesinger asked.

“It was a well-known case and that photograph that they showed him had been one that had been in the newspaper,” Iredale replied.

But Kevin Brown also said he may have met someone named Claire in the 80s, and that he might have had sex with her. Iredale says Kevin Brown was just being honest.

“I think that he said that he had met a Claire, but the Claire that he was talking about was a woman who was 30 years old,” said Iredale.

Even the investigator seemed to acknowledge in the affidavit that this woman did not sound like Claire Hough. But remember, Kevin Brown had allegedly also told a friend that he photographed a girl who was found dead on the beach.

“The man to whom this statement is attributed says he never said such a thing,” said Iredale.

Gretchen Von Helms argues investigators had tunnel vision and interpreted everything Kevin Brown said as evidence of his guilt. She says that’s what happened when Brown told a detective “I had no idea” Claire was 14.

“They immediately think the — the suspicious, guilty version of that versus, ‘Oh, my God. You’re telling me this awful crime,'” Von Helms said. “A normal citizen, when told about this awful crime would say, ‘Oh, my Gosh! This poor child was 14? … How awful this is!'”

The attorneys admit Kevin Brown’s personality did little to help him during the investigation.

“He was one of the worst public speakers … let’s say, in the history of the San Diego Police Department lab,” said Iredale.

“He was kind of like a nervous Nelly,” said John Durina.

Retired criminalists Durina and Jim Stam say Kevin Brown was, at best, a shaky witness for the police in court cases.

“Whenever he got confronted, he got very nervous and very upset,” Durina said. “He wanted to agree. He wanted to please them.”

“I think that his personality is set up so that I could almost convince him to say anything. You can bully him. It’s easy to bully him,” said Stam.

But Kevin Brown’s shyness or awkwardness cannot explain his DNA on that swab. Several swabs were taken from inside Claire during the autopsy. The medical examiner tested one of them in 1984 and found nothing. Another swab was sent to the San Diego Police Department lab and that’s where the lawyers say the trouble began.

“It was not kept in a way that would ensure the integrity of the evidence,” said Iredale.

It was the early 80s before much was known about DNA, and the procedures now used to prevent contamination did not exist.

“How different were the procedures back then?” Schlesinger asked Stam.

“A lot,” he replied.”We didn’t wear masks — that’s for sure.”

Kevin Brown did not work on the Claire Hough case, but he worked near the criminalist who processed the evidence — including that swab where a minute amount of Brown’s DNA was later found.

“The swab itself was put to dry in the open air…” said Iredale.

“Without a cap,” added Von Helms.

“On a table near where Mr. Brown worked,” Iredale continued. “Everything that was able to be airborne could have gone and touched that swab.”

“The problem though, with this case is, seems to me that the allegation is that this isn’t sweat or spit. … It’s his semen. … How would his semen get on a swab?” Schlesinger asked.

“You can still have cross contamination of semen because they had to have fresh samples of semen in the San Diego lab,” said Von Helms.

At the time of Claire Hough’s murder, criminalists would often bring their own seminal fluid to the lab and use it to ensure the chemicals used to detect semen were working correctly. Durina and Stam believe that all the criminalists in the lab did it.

“I think Kevin was doing that same thing,” said Durina.

The San Diego Police Department, however, insists that contamination was not possible. But the retired criminalists know what they saw.

“Most likely, Kevin’s semen standard was in that lab and several analysts may have even had it. It may have been even used on that particular — on Miss Hough’s case,” Durina explained.

“We didn’t switch gloves back then, either,” Stam explained. “So let’s say the analyst took Kevin’s semen sample, wearin’ the same gloves and then handled the deep vaginal swab … there’s a logical explanation for the contamination.”

Cross contamination does happen. There have been cases of lab technician’s DNA ending up on evidence documented in several states and at least four other countries. Given the procedures used in the lab at the time and the lack of other solid evidence, Kevin Brown was assured that the case against him was weak.

“And I believed … that they lacked the evidence necessary to charge Mr. Kevin Brown with these murders,” said Von Helms.

But by mid-2014, the stress of the investigation, which was dragging on, was making Kevin Brown very anxious.

“I said, ‘Call ’em and get it straightened out.’ And he said, they just said, ‘You know you killed her and you may as well confess.’ And he hung up the phone and he said, ‘I didn’t even say anything back to them … because I didn’t know what to say at this point.’ He said, ‘I didn’t do it and they’re never going to believe me,'” an emotional Rebecca Brown said.

Rebecca Brown hoped that their nightmare would soon end, but it wouldn’t end in a way that anyone expected.

WAS KEVIN BROWN ANOTHER VICTIM?

On the morning of Oct. 20, 2014, Rebecca Brown came home from work and found her husband’s Bible sitting on the table. In it, he had underlined a Psalm about being wrongfully accused.

“His watch was there. And his cell phone was there. And so I asked my mother, ‘Where is Kevin?’ … And she just said he went somewhere. He went out … he was cleaned up, he’d shaved, he’d showered, looked nice and said, ‘I have things to do,'” said Rebecca Brown.

Kevin Brown didn’t come home that night. The following day, Rebecca got the news she feared most.

“And I was just sitting there waiting and then there was the door knock. And it was the detective and he said, ‘ We found your husband. And he’s gone,'” she said in tears.

Rebecca Brown

A ranger at Cuyamaca Rancho State Park, near where the Browns had a vacation cabin, had found Kevin hanging from a tree.

“Were you surprised, even after everything that he’d been through?” Schlesinger asked Rebecca Brown.

“We tried — I tried to keep his spirits up,” she said through tears.

“You thought you had kept him safe,” said Schlesinger.

“Yeah,” Rebecca Brown sobbed.

Rebecca Brown is adamant that her husband’s suicide was not an admission of guilt.

“I totally understand why he did it,” she said. “… he knew there would be people … who would think even if he went to court and was found not guilty — that would believe it … And this was gonna tarnish his reputation that he prided himself in.”

“He didn’t escape that, of course. After he died, the police held a news conference,” Schlesinger noted.

“Yeah,” she replied.

Three days after his death, the San Diego Police Department publicly named Kevin Brown as one of two suspects in Claire Hough’s murder.

Press conference: We were able to establish a very strong case that Ronald Tatro and Kevin Brown were the suspects in the murder of Claire Hough. And also an arrest for Brown would be forthcoming.

“You never had enough to arrest him in his lifetime. And now that he’s gone you’re just going to just say, ‘He did it, case solved, it’s done,'” said Rebecca Brown angrily.

“Why do you think they did that?” Schlesinger asked.

“Because this can be very tidy for them,” she replied.

Rebecca Brown has answered the police charges with charges of her own. She has filed suit against two police detectives for misconduct and wrongful death.

“He was not a rapist and a killer. He was a quiet, good man,” Rebecca Brown addressed reporters. “And I’m hoping the legal system will help set things right.”

The San Diego Police Department refused “48 Hours”‘ request for an interview. But Penny and Sam Hough, Claire’s parents, have the answers they need.

“We’re confident in the San Diego Police Department and their discoveries,” said Penny Hough.

The Hough family says after 30 years, the details surrounding their daughter’s death are not as important to them as remembering her life.

“We’ve learned to live with her death. We’ve learned to live without her physical presence in our family,” said Penny Hough.

“To us, what’s important is what Claire was, and what she meant to us and to the people around her,” said Sam Hough.

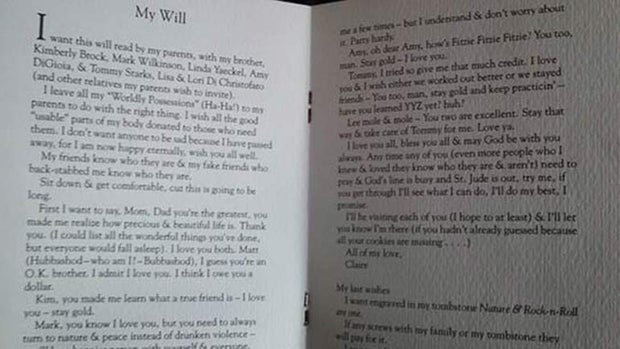

Hough family

Claire left her parents with a lot of memories. And at 14, she had the foresight to leave a will telling her family and friends that she loved them and not to be sad.

“‘You’ve made me realize how precious and beautiful life is. Thank you. I wish I could list all the wonderful things you’ve done, but everyone would fall asleep. I love you both,'” Sam Hough read aloud from the document.

“What did it mean to you that she had done this, and she had written this?” Schlesinger asked.

“It’s always a puzzle why she did it. But it is also a treasure,” Penny Hough replied.

But the family of Barbara Nantais, the first victim in this case, still has as many questions about her murder as they did in 1978.

“… the reality of what happened to her is so hard,” Sue Nantais said to her mother, Judy, at Barbara’s graveside.

“I wanted to know her. I wanted her to have a life,” said Judy Nantais.

Police now say Barbara and Claire’s cases are not connected.

“I would like a viable suspect,” Judy Nantais said. “But we don’t have one.”

Ronald Tatro was in prison for rape at the time of Barbara’s murder and Kevin Brown was attending college in Sacramento, 500 miles away.

“What has it done to you over the years, especially with the developments in Claire’s case to see this case still remain open?” Schlesinger asked Barbara’s boyfriend, Jim Alt.

“It’s devastating,” he replied. “We want answers. We wanna know what they’re doing to solve this.”

Even today, Jim Alt says he’s suffering from survivor’s guilt. It’s stayed with him even though Barbara’s father, Ralph, sent him a letter long ago apologizing for having blamed him for her death.

“‘I want you to know that I don’t hold you responsible for Barbara’s death. When I was grieving over her death, I needed to blame someone. And since she was with you, I lashed out at you … “Ralph Nantais read from the letter.

“‘Jim, you were trying to be alone with Barbara is probably what every red-blooded American boy dreams of. Unfortunately, the time you spent together turned out to be a disaster. But, the chance of that happening was probably one in a million. … Yours truly, Ralph Nantais,'” Alt read aloud.

CBS News

“It still is hard for you to read that without choking up?” Schlesinger asked of the letter.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

“He’s absolving you in a way. Does that help you?”

“When I first read it, it did. But, you can’t hide what happened,” Alt said. “Because of a decision Barbara and I made, she never came home. So, I — I own part of that decision. And I’ll take that to the grave with me.”

In 2020, a federal jury awarded Rebeccca Brown more than $6 million in her wrongful death lawsuit.