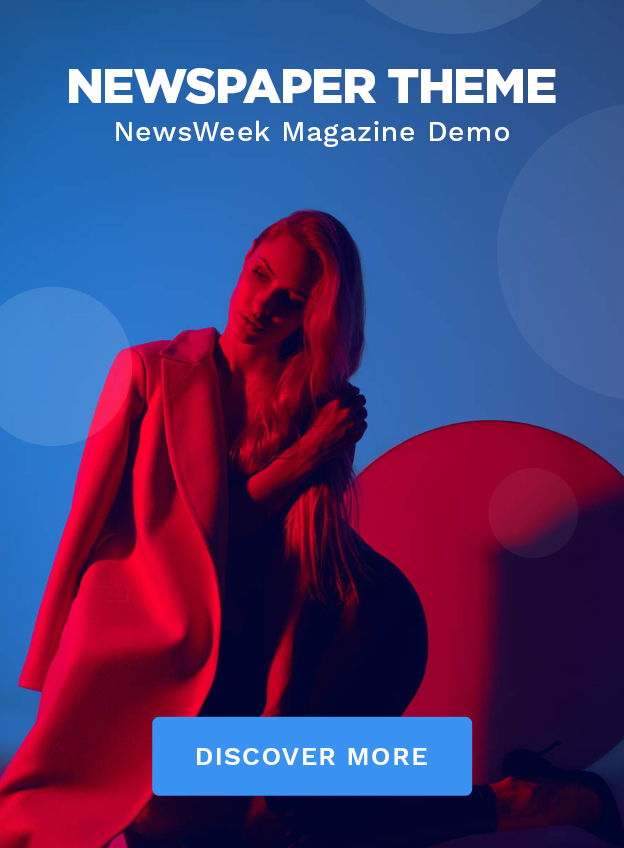

The newer TESS mission covers almost the entire sky, compared to the small patch of sky observed by Kepler.

Kepler stared at only a few small fields (blue) of about 116 square degrees each in the sky during its lifetime: one in Cygnus and several along the ecliptic plane. TESS’ four cameras (yellow, orange, red, and purple) are is designed to cover nearly the entire sky every two years. The newer telescope observes each of 13 sectors, measuring 24° by 96° apiece, for 27.4 days before moving on to the next. This animation compares all four years of Kepler observations to the first six years of data sky covered by TESS. Credit: Maps: Astronomy: Roen Kelly, after https://tess.mit.edu. Milky Way map: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio. Gaia DR2: ESA/Gaia/DPAC. Projection: G.Projector 3 — Map Projection Explorer. Animation: Darren Case.

How is TESS able to spot more planets in the sky than Kepler could?

Doug Kaupa

Council Bluffs, Iowa

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) has outpaced the now-retired Kepler mission in discovering planets and planet candidates primarily because of the former’s significantly larger survey area. It covers almost the entire sky compared to the small patch of sky observed by Kepler. In order to maximize coverage across the sky, TESS observes roughly 1 million stars amenable to planet detection for roughly 27 days before moving on to another set of targets. Tens of millions of such stars have been observed since the start of the mission. Meanwhile, Kepler observed a smaller number of stars but for a much longer, sustained amount of time, watching about 150,000 Sun-like stars for four consecutive years.

Essentially, TESS has access to a significantly larger pool of stars in which it can find planets. The TESS mission has also operated for longer than Kepler, spanning nearly six years (and counting) compared to Kepler’s four.

The different observing strategies adopted by Kepler and TESS were chosen to support their specific scientific goals, and both missions have advanced our understanding of exoplanetary systems in unique ways. Kepler’s focused observations provided crucial insights into the demographics of small exoplanets with orbital periods up to several years, as well as the architectures of multiplanet systems around Sun-like stars. Kepler also provided the best dataset we have for understanding the prevalence of Earth-like exoplanets in our galaxy.

TESS complements Kepler by identifying exoplanets around a more diverse array of stars and their environments. Furthermore, by focusing on detecting planets around bright stars across the entire sky, TESS is finding targets that are perfect for follow-up observations to measure planet masses and atmospheric compositions. Together, Kepler and TESS have been significant contributors to the discovery and understanding of exoplanets.

Michelle Kunimoto

Torres Postdoctoral Fellow, MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts