Computerized telescope mounts and plate-solving software make it easy to return to the same celestial location every night.

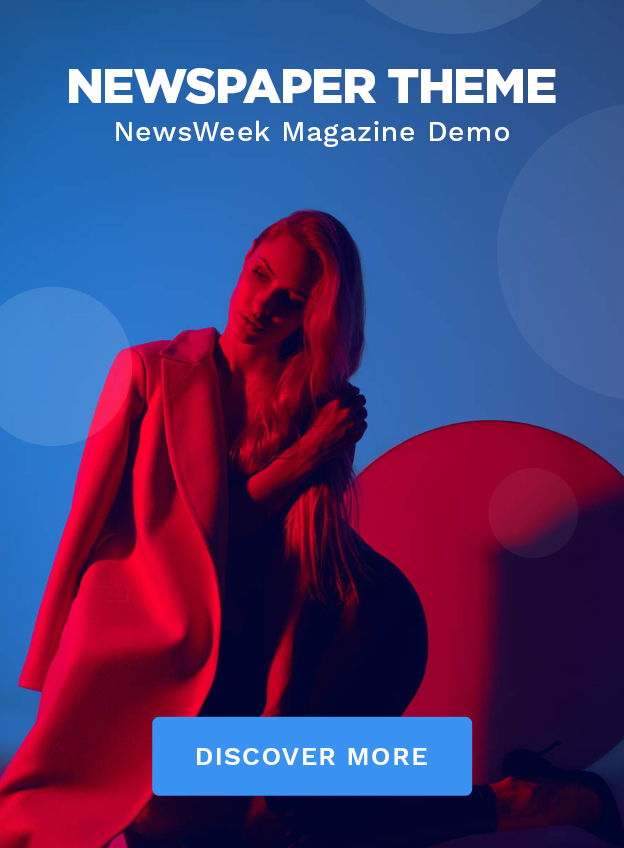

This deep image of the large emission nebula NGC 7822, taken from Dayton, Ohio, comprises a total of 27 hours of exposure time over a span of four weeks in 2022. Credit: Molly Wakeling

Many astrophotos feature exposures of 12 hours or more. Since nighttime darkness is only about this long, this implies multiple exposures on different nights. How does one set things up to get the exact same location, and avoid parallax error due to Earth’s rotation and orbit?

Jose G. Riera

St. Augustine, Florida

You are correct, many long-exposure astrophotos span multiple nights. I typically stay on a target for months at a time, especially when I’m living in a cloudy place. Plus, viewing locations often have a tree or a building or some other obstruction, meaning that many objects are only visible a few hours per night. And because it is best to image objects that are at least 20° or so above the horizon to avoid the thickest lines-of-sight through the atmosphere, your window may be further limited.

Astrophotos usually consist of dozens to hundreds of multiple-minute exposures that are “stacked” together to reduce noise and bring out the dim celestial object being imaged. The computerized telescope mounts astrophotographers use to track the sky know where to point based on the mount’s latitude and longitude, and the date and time. With the help of plate-solving software that uses star patterns to identify where an image is located on the sky, it is easy to return to the exact same celestial location every night.

The effect of parallax, the shifting of nearer stars relative to those farther away as Earth travels around the Sun, is negligible — the nearest star, Proxima Centauri, only appears to move 0.77″ over the course of a year, which is only a few camera pixels with long-focal-length telescopes and is less than 1 pixel for shorter telescopes.

Molly Wakeling

Contributing Editor