metamorworks

Market Review

Global equity markets inched higher this quarter, belying significant underlying divergence between sectors, as stellar returns in Information Technology, especially within the semiconductor industry, balanced out declines in other sectors.

Monetary policies continued to diverge in developed markets. The US Federal Reserve maintained the federal funds rate within the range of 5.25% and 5.5%, reflecting a cautious stance aimed at containing inflation while supporting growth. Despite earlier forecasts suggesting multiple rate cuts in 2024, markets are now pricing in just two. The Bank of Japan also kept rates stable but further reduced its bond purchases; Governor Kazuo Ueda indicated that further rate hikes remain a possibility despite signs of economic weakness, including weak private consumption and rising living costs. In contrast, the European Central Bank lowered its key rate to 3.75% from 4%, making its first cut since 2019, even as wage cost pressures persist.

There was little change to the shape of the US yield curve, which remains inverted at roughly the same level as the previous quarter, indicated by the 10-year minus 3-month spread. Such inversions, where short-term rates rise above long-term rates, has frequently occurred in advance of past recessions, and typically un-inverted soon before the recession’s start. However, the current inversion has persisted for nearly two years, making it the longest in post-war history and casting doubt on its reliability as a recession indicator in the current context.

MSCI World Index Performance (USD %)

|

Sector |

2Q 2024 |

Trailing 12 Months |

|

Communication Services |

8.2 |

37.6 |

|

Consumer Discretionary |

-2.2 |

9.8 |

|

Consumer Staples |

0.3 |

2.7 |

|

Energy |

-1.1 |

16.6 |

|

Financials |

-0.2 |

24.5 |

|

Health Care |

0.6 |

11.7 |

|

Industrials |

-2.1 |

16.3 |

|

Information Technology |

11.5 |

38.4 |

|

Materials |

-3.3 |

8.5 |

|

Real Estate |

-3.1 |

5.6 |

|

Utilities |

3.5 |

5.8 |

|

Geography |

2Q 2024 |

Trailing 12 Months |

|

Canada |

-1.9 |

9.5 |

|

Europe EMU |

-2.1 |

10.7 |

|

Europe ex EMU |

4.1 |

14.2 |

|

Japan |

-4.2 |

13.5 |

|

Middle East |

-4.0 |

24.2 |

|

Pacific ex Japan |

2.5 |

6.9 |

|

United States |

4.1 |

24.7 |

|

MSCI World Index |

2.8 |

20.8 |

|

Source: FactSet, MSCI Inc. Data as of June 30, 2024. |

|

Companies held in the portfolio at the end of the quarter appear in bold type; only the first reference to a particular holding appears in bold. The portfolio is actively managed therefore holdings shown may not be current. Portfolio holdings should not be considered recommendations to buy or sell any security. It should not be assumed that investment in the security identified has been or will be profitable. A complete list of holdings at June 30, 2024 is available on page 9 of this report. |

While inflation appears under control in most countries and bond yields remain stable, recent election results have introduced new volatility in developed markets. In Europe, far-right parties made significant gains in the parliamentary elections in the European Monetary Union (‘EMU’). French President Emmanuel Macron reacted to his party’s rout at the ballot box by hastily calling for snap legislative elections, prompting French markets to fall. In Germany, Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s center-left Social Democrats also received a drubbing and are now polling behind the extreme- right wing Alternative for Germany (AfD) party, although with elections there more than a year away, markets were calmer. In another anti-incumbent outcome, the Labour party secured the majority in the UK Parliament, bringing an end to Conservative Rishi Sunak’s 20-month tenure as Prime Minister, and to the Tories’ 14-year hold on power.

The ongoing weakness of the Japanese yen remained the headline story in currency markets, as it fell an additional 6% against the dollar, reaching its lowest level since 1990. The decline appears to be caused by local investors seeking higher real yields outside their domestic market, as policies remain targeted at stimulating inflation in the economy. Emerging market currencies in Latin America fared even worse: the Brazilian real and Mexican peso both dropped roughly 10%, weighed down in part by narrowing interest-rate differential with the US dollar.

When viewed by sector, last quarter’s pattern of strong gains in IT and Communication Services continued. IT was the best performing sector, though returns within the sector were bifurcated, as industries with direct artificial-intelligence beneficiaries such as semiconductors & semiconductor equipment and technology hardware & equipment surged by double digits, while software & services shares rose only 2%. Communication Services also outperformed, as Tencent (OTCPK:TCEHY) and Alphabet (GOOG,GOOGL) both rallied, offsetting underperformance by Meta Platforms (META). Energy and Materials both declined.

Despite the strong showing of US tech companies, European markets outside the monetary union matched the returns of the US market. Within the eurozone markets fell, as election results weighed on returns in France and Germany. Japan also declined, unable to overcome the yen weakness. In Emerging Markets (EMs), Taiwan soared due to returns from chip powerhouse TSMC (TSM). Indian stocks recovered to new highs, and the heavyweight Chinese market rebounded with a 7% gain. These markets offset poor returns in other EMs such as Brazil and Mexico.

As in the previous quarter, strong share-price gains from US-based heavyweights pushed indices higher and contributed to differing style returns. The MSCI World Index would have finished nearly flat without the positive contribution from Nvidia (NVDA), Apple (AAPL), and Alphabet. Shares of faster-growing companies once again outperformed their slower-growing peers, with the top quintile of growth stocks returning more than 11% while the other 80% of the market combined to return next to nothing. Stocks of higher-quality companies, characterized by lower leverage and more stable returns on capital, fared better than those of lower quality. The MSCI World Quality Index, which features large weights in Nvidia along with other tech companies, outperformed the core index by 300 basis points (bps). Cheaper stocks also lagged behind more expensive ones. In Japan, the return spread between the cheapest and most expensive quintiles was 700 bps, bringing the year-to-date gap to 1,100 bps.

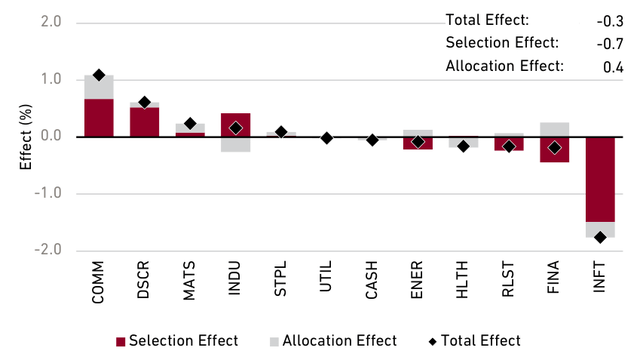

Performance and Attribution

The Global Developed Markets Equity composite rose 2.5% gross of fees in the second quarter, just behind the 2.8% gain in the MSCI World Index.

The portfolio nearly kept pace with the index despite not owning the single largest contributor to the index’s rise: Nvidia. Investors, encouraged by another quarter of record sales and excited over a 10-to-1 share split, pushed the chipmaker’s share price to new highs and its market capitalization to above US$3 trillion, as it vied with Apple and Microsoft for the title of world’s most highly valued company.

The negative selection effect from the absence of Nvidia was partially offset by other holdings in the IT sector that are part of the semiconductor value chain, including Applied Materials (AMAT), Broadcom (AVGO), and TSMC, all of which outperformed the sector and market. Relative returns were also hurt by our underweight to Apple, which rallied after unveiling a suite of new AI features for its phones, tablets, and laptop computers.

Also within IT, our holdings in software and services underperformed. Shares of Salesforce (CRM) and Accenture (ACN) declined, before regaining some ground late in the quarter as management commentary during the companies’ quarterly earnings suggested a coming wave of spending on AI.

In Communication Services, Alphabet, Pinterest (PINS), and Tencent were significant positive contributors. Pinterest shares jumped after reporting year-over-year revenue growth of 23% for the first quarter, which exceeded the market’s expectations and supports the thesis that the changes being implemented by the relatively new management team are leading to improved platform engagement and monetization. Alphabet’s Google division said cloud revenue rose 28%, with strong growth from segments hosting AI capabilities.

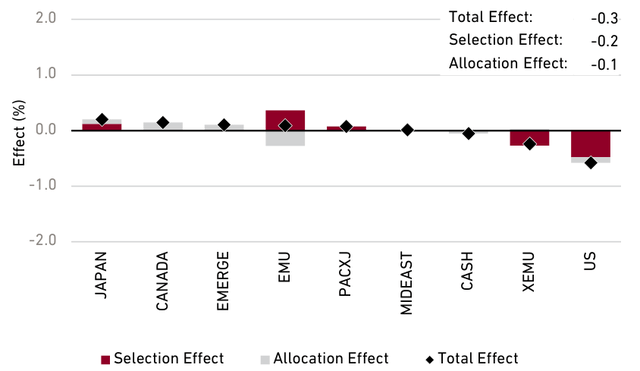

By region, the strength in tech hardware and relative weakness in software and services largely explains the negative contribution from the US.

Second Quarter 2024 Performance Attribution

Sector: Global Dev. Markets Equity Composite vs. MSCI World Index

Geography: Global Dev. Markets Equity Composite vs. MSCI World Index

| Source: Harding Loevner Global Developed Markets Equity composite, FactSet, MSCI Inc. Data as of June 30, 2024. The total effect shown here may differ from the variance of the composite performance and benchmark performance shown on the first page of this report due to the way in which FactSet calculates performance attribution. This information is supplemental to the composite GIPS Presentation. |

In the EMU, Schneider Electric’s (OTCPK:SBGSF) continued strength was offset by weak performance from Dutch payments processor Adyen (OTCPK:ADYEY). Schneider’s position as the world’s leader in electrification solutions was reaffirmed with its announcement of better-than-expected revenue and an increased backlog of orders. Adyen’s shares fell after reporting 21% growth in first-quarter revenue, which was in-line with expectations. Its take rate fell, raising investor concerns that the company may be cutting prices in response to competitive pressure; however, we agree with management’s interpretation that the fall in take rate was due to a temporary shift in its mix of clients to lower-margin large customers.

The portfolio’s off-benchmark EM stocks were helpful, particularly Taiwan’s TSMC—a key supplier to Nvidia—as well as China’s Tencent. Tencent reported that profitability improved across its business segments from better sales of higher-margin products, strong revenue growth in video advertising, as well as cost-cutting in its unprofitable divisions.

Perspective and Outlook

Now that the economy and capital markets have recovered from the turmoil of COVID-19-related lockdowns and shortages, breathtaking innovations—from generative AI to GLP-1 diabetes and obesity drugs—are rekindling hope for great prosperity. Of course, not every discovery or newfangled technology moves the economic needle, but long-term prosperity is generally reliant on innovation. And although the threats of war, economic recession, and social unrest continue to loom, one lesson from the COVID-19 pandemic and every crisis before it is that if anything in the world is guaranteed, it’s that the inherent ingenuity of humans will always lead to more innovation.

Growth investing, which is predicated on exposure to continued waves of innovation, frequently has long periods of outperformance, and it is where an investor ought to want to be. The challenge is correctly identifying which growth companies will rise to the top, as a small proportion of stocks typically accounts for the vast majority of wealth creation. Even for the strongest companies, the pursuit of growth can be a treacherous journey.

Just like the summer sunshine and heat, filled with joie de vivre, also delivers thunderstorms and hurricanes, the summer of growth equity—if that’s what this current market environment is—can be full of surprises and setbacks, too.

A common cause of value destruction that can surprise growth investors is competition. Naturally, promising fields attract ambitious minds, and the success of the companies they create invites competitors. To keep growing, a business must outrun its rivals.

One of the great races of our time is the relentless pace of new AI capabilities and products being unveiled by tech startups and incumbents. A pivotal moment came in late 2022, when OpenAI, a startup backed by Microsoft (MSFT), launched its ChatGPT 3.5 generative-AI model, which can produce text responses to natural-language prompts. The consumer-friendly functionality of the chatbot made the wider world more aware and appreciative of the possibilities of generative AI, particularly for speeding up workplace processes. Since then, AI chatbots have advanced to generating images, short videos, and—in the case of GPT-4o, released in May—voice responses. Adobe (ADBE), the dominant provider of graphic-design software, is an example of a company trying to stay ahead in this race, as AI allows competitors such as the startup Canva to try to pitch users on an easier way to make content. However, Adobe’s data prowess, scale, and copyright protections afford it a sizable advantage, which has been furthered by the strength of its own AI model and chat assistant, Firefly. The company recently raised full-year forecasts as Firefly begins to generate revenue.

Not every race is as fast paced as the one unfolding for AI tools. Drug development, for example, moves slowly by technology’s standards, yet the stakes are high and the process similarly nerve-racking. Consider the outcome of the competition between Vertex Pharmaceuticals (VRTX) and Merck (MRK) more than a decade ago over a new generation of medicines for hepatitis C. After many years of research and development, Vertex and Merck had produced rival drugs that were more effective at ridding patients of the virus than existing treatments. This led to both drugs winning US regulatory approval just days apart in 2011. But as the companies

shifted their focus to marketing their therapies, another competitor, Pharmasset (later acquired by Gilead), unveiled a treatment that was significantly more effective. For Vertex and Merck, the race was over. They had no choice but to withdraw their drugs from the market. But even Gilead’s monopoly position didn’t last, as new entrants eventually delivered treatments with similar efficacy and safety profiles and made the rare industry move to compete on price. (Fortunately, Vertex’s business was not devasted by the hepatitis C setback, due to the success of its drug for cystic fibrosis, which arrived around the same time and became a source of long-term growth.)

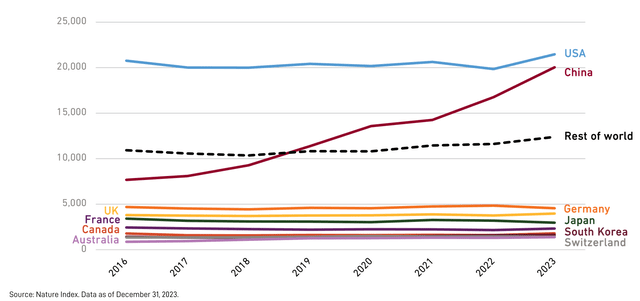

Competition between companies is influenced not only by innovation but also by the competition between nations. One way to try and quantify that competition is the Nature Index, which is compiled by the publisher of the scientific journal Nature and tracks contributions to research articles published in the most reputable natural-science and health-science journals. It is a good indicator of a nation’s capabilities in fundamental research, which is part of the ecosystem that supports innovation at the company level (other parts of the ecosystem include education and venture-capital spending). The index shows that China, which was a distant second in terms of research contributions in 2014, has risen over the past decade to stand neck and neck with the US.

This is meaningful because the strength of fundamental research in the US and Europe over the last few decades—centuries even— has translated into enormous leads in the fields of technology and life science. Recently, however, we have started to see Chinese companies pull ahead in new industries such as electric vehicles, in part because of China’s mastery of fundamental sciences and technologies, such as materials science and electrical control. This technological lead is one reason we don’t invest in any European or Japanese car manufacturers, which were the frontrunners in the era of the internal combustion engine.

Nature Index: Science papers credited to each country over the past eight years

The “race” analogy shouldn’t leave the impression that companies in each industry are all operating on the same racetrack, in which the routes, conditions, and rules are clear and fixed. The reality is that everything around them is always changing—from technology to the climate to the world’s economic order—and so businesses must blaze their own trail. It’s why we can’t assume that the most profitable and fastest-growing businesses will stay that way forever. Today’s winners will have to evolve accordingly to maintain their positions.

Sometimes, this means using thoughtful mergers and acquisitions to entirely reinvent a business. Perhaps no company has done this more successfully than Danaher (DHR), which has come a long way from the small hodgepodge of manufacturing businesses that it once was. Sometime in the 1990s, the company began to recognize that the industry it was in, primarily automotive parts, was going to face challenges, and so it began using its cash flow to gradually acquire its way into slightly better businesses in the areas of science and technology. As a result of those many years of dealmaking, Danaher is now a leading global life science and diagnostic innovator with more than US$4 billion in annual profit.

We can contrast Danaher with General Electric and 3M. They were great businesses 20 and 30 years ago, but their industries have matured and deteriorated, and neither company evolved. It is why they were sold from this portfolio long ago. Meanwhile, many of our holdings— Thermo Fisher Scientific (TMO), Atlas Copco (OTCPK:ATLKY), and Schneider Electric, to name a few—are those that, like Danaher, have adapted. Thermo Fisher, for example, went from selling the most basic health-care consumables, such as glassware and chemicals, to becoming a highly respected producer of high-end, cutting-edge life-science instruments, including mass spectrometers.

Any one company is subject to perils, but that is why we have some 50 portfolio holdings. One of our firm’s bedrock principles is an insistence on broad diversification and exposure to sectors around the world. Another is that we seek to own companies of the highest quality that can deliver sustained high profitability from riding these waves of innovation. Without quality, the duration of any growth would otherwise be called into question. That is why our research process is geared to search only for businesses that display financial strength, competent management teams, and a sustainable competitive advantage.

By innovation, we also don’t just mean AI and other headline-grabbing developments. Companies pioneering less widely known advances in their fields include Intuitive Surgical (ISRG) with its robotic-surgery capabilities, Tradeweb (TW) with its electronic-trading platform for the bond market, and Alcon (ALC) with its ophthalmology instruments. In each case, innovation is reinforcing the company’s competitive advantages, which is translating to resilient profits and cash flows across economic cycles. We think it is through this combination of financial and business-franchise quality, innovative growth, and diversification that we can overcome the pitfalls of investing in a cycle of booms and busts.

Portfolio Highlights

In 1967, leading scientists and engineers inside the Dutch conglomerate Philips had a tremendous achievement to showcase at the company’s annual research exhibition. They had developed a six-barrel step-and-repeat camera system for semiconductor manufacturing—essentially, the predecessor to the lithography machines used today. Although the exhibit initially attracted a large crowd of fellow researchers and top Philips executives, it wasn’t long before the executives turned their attention to a nearby booth that was displaying new features of a different product, the washing machine.

In the decades that followed, Philips became a leader in consumer electronics and health-care equipment, and the camera system technology—a tiny moonshot project it never seemed to prioritize—became ASML, a leading supplier of the intricate machinery used to produce semiconductor chips. The latter continued to take innovative leaps, and it has been rewarded. ASML now has a market value nearly 20 times larger than that of its former parent.

This quarter, nothing—certainly not washing machines—could divert attention away from ASML or its peers Nvidia and TSMC. The three semiconductor stocks were responsible for a disproportionately large percentage of the overall market return. Two of them, ASML and TSMC, have been portfolio holdings since 2021, while we exited Nvidia in the first quarter after more than five years. Their strong performance is quite deserving, given that the competitive structure of their industry, oligopoly or near monopoly, is more favorable than most we encounter. But just a few years ago, as the personal computer and mobile phone cycles ran their course, the outlook for chip demand was much less sanguine.

The tech world has long subscribed to Moore’s Law, an observation and prediction that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit doubles every two years with a minimal rise in cost. But as it has become increasingly difficult and costly to shrink the size of transistors any further, the fear has been that without a technological breakthrough, the computational power of chips will hit a ceiling. One promising technology that has emerged to counter this fear is extreme ultraviolet (‘EUV’) lithography.

Think of a lithography machine as a large camera that uses light to transfer precise patterns onto a wafer’s surface, which is then diced into chips. The shorter wavelengths of EUV radiation can print a sharper image of tinier details, thus allowing for smaller transistors. But using a different light source also created a host of challenges that had to be solved. After spending years working to improve the performance of its EUV machines, from throughput to overlay accuracy to uptime, ASML has now shipped more than 100 of them to customers, with some configurations costing well north of US$100 million. As it was working to perfect these EUV machines, ASML also began to develop a next-generation technology called High NA (for numerical aperture), which can print even finer features on a wafer. After a decade of research and development, it shipped its first High NA machine in December 2023, leaving its competitors even further behind. With these tools, the semiconductor industry can potentially develop more powerful and energy-efficient chips to meet the surging demand for computing power coming from fields such as AI, autonomous driving, and the internet of things.

Shrinking the transistor through innovations in lithography is still just one step to produce more powerful chips. The transistors also need to become more interconnected, thus allowing for a higher number of them to sit on a single chip (our Fundamental Thinking article “ Third Law: How a Pair of Chip Companies Came to Hold the Keys to Everything” details this trend). In April, TSMC unveiled its plan to do this, which will advance chip technology by two generations—from the current N3 (three nanometer), to N2, and then to A16 (meaning 1.6 nanometers, or 16 angstrom). Currently, a typical graphics processing unit (GPU) used to train an AI model has over 100 billion transistors. TSMC Chairman Mark Liu forecasts that within a decade that figure will rise to more than 1 trillion. Such a steep trajectory is a great manufacturing challenge, and if the company is successful, it will be a great testimony to TSMC’s engineering capabilities.

Even with such a formidable position, these industry leaders have had their share of ups and downs. We don’t believe we can add much value in trying to predict industry cycles or time the tipping point of demand—whether for hardware companies such as ASML and Nvidia or the software and IT services companies we wrote about last quarter, such as Adobe, Salesforce, Accenture, and Globant (GLOB). Earlier this year, several software and services companies reported disappointing earnings, as overall IT spending remains muted amid high interest rates and ongoing economic and geopolitical uncertainty. But secular growth appears to be underpinned by the innovations described above, as well as the race to introduce value-added tools that use AI to solve business problems. Although the market remains enamored with Nvidia, which trades at a high price-to-earnings ratio, we continue to believe that as large companies embrace generative AI, software and services businesses will become primary beneficiaries of the AI trend.