400tmax

Introduction

Per my July article, Google (NASDAQ:GOOG) (NASDAQ:GOOGL) continues performing well as the world embraces AI. Since that time, the August 5, 2024 Memorandum Opinion court document has come out, and it is packed with information on Google’s business advantages. My recommendation for anyone considering an investment in Google, Apple (AAPL), Microsoft (MSFT) or any company in the digital advertising space is to read this court document. Before going through the document, one should know key acronyms such as general search engine (“GSE”), specialized vertical provider (“SVP”), product/shopping listing ad (“PLA”), mobile application distribution agreement (“MADA”) and revenue share agreement (“RSA”). Regarding PLAs, they are discussed heavily despite the court document saying that in 2020, text ads made up about 80% of Google’s search ads by revenue.

I’ve been invested in Google for many years, and I already knew they had a tremendous business. Having said that, this court document sheds new light on some of Google’s advantages. This court document also presented tremendous regulatory risk for Google given the ruling on text ads.

My thesis is that Google has a great business, but they face serious regulatory risk.

We have to understand Google’s excellent business in order to appreciate the regulatory risk, so the first part of the article focuses on the business. We then move to the ruling from the court document and look at potential regulatory consequences.

When we say “the court document” throughout this article, we’re talking about the above document from August 2024.

Development And Investments

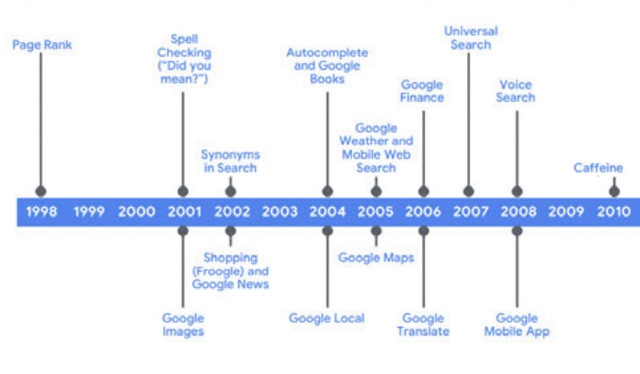

Google didn’t put together their enormous business overnight. Development and investments were essential over the years to get to the environment we see today. The court document does a nice job showing how Google has made continual investments which expand the use of search. Numerous examples of innovation are given:

Early Google Innovations (Memorandum Opinion court document)

Google doesn’t broadcast all their developments/investments for competitive reasons. One signal not shown above is Navboost, and it has been around since about 2005 per the October 2023 testimony with Google Search VP Pandurang Nayak. The court document describes Navboost as a memorization system:

Navboost is another signal that pairs queries and documents through memorizing user click data. It allows Google to remember which documents users clicked after entering a query and to identify when a single document is clicked in response to multiple queries.

Google Innovations (Memorandum Opinion court document)

In addition to Navboost, another memorization system not shown above is Query-based Salient Terms (“ QBST”). Per the court document, it is a signal that helps respond to queries by finding words/phrases that are tied together. We see an example with “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue” and “White House.”

Above, we also see Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (“ BERT”) in 2019 and Multitask Unified Model (“ MUM”) in 2021. I wrote about both in my August 2021 article, and MUM is important in this article when we talk about scale and AI. Search is about understanding language, and BERT recognizes the importance of words such as “to” and “for.” Before BERT, a user searching for “Brazil traveler to USA need a visa” might see results for information about traveling to Brazil. BERT knows a search like “can you get medicine for someone pharmacy” should have info on whether family members can pick up prescriptions. MUM turns up the dial with respect to context, and it is 1,000 times more powerful than BERT. If a person has hiked Mt. Adams in Washington State and then starts asking questions about what should be done differently to hike Mt. Fuji in Japan, MUM understands how to approach this.

Google has invested heavily in keyword matching, which helps both advertisers and consumers. It is unrealistic for advertisers to guess all the keyword combinations customers may use for their products, so Google created an automated system which does the matching.

Google’s planning and innovation investments have brought about tremendous results; they have been instrumental in building up scale, which makes the economics of the business very nice.

Scale

The court document describes Google’s treasure trove of user data as their magic:

Early on, Google understood that the information gleaned from user queries and click activity were a strong proxy for users’ intent and that such information could be used to deliver superior results. (“[M]ost of the knowledge that powers Google, that makes it magical, ORIGINATES in the minds of Google users.”); (“As people interact with the search results page, their actions teach us about the world.”).

Google saves data at every stage of the search process and this information is used to improve their search engine. Oftentimes a question and answer on Google are more involved than one might think. Suppose I search for “football” from my phone in New York City. By using my phone for the search instead of a desktop or laptop computer, I’ve signaled to Google that local results might be important. By searching from the US instead of the UK, I’ve signaled that we’re probably talking about the American pigskin game and not soccer. Google saves these and other signals for every search, along with the search phrase itself and the resulting clicks from the search engine results pages (“SERPs”). Google collects more information than anyone, and they use it to continually improve what is already the best search engine in the world.

We use the term “clicks” above loosely. In addition to the clicks themselves, Google also keeps track of how much hovering there was, how long it took to make the click, how long it took for the user to come back to Google and other factors. Per the court document, users make Google better by sending all these signals (emphasis added):

There are different types of user data. Click data, for example, includes the search results on which a user clicks; whether the user returns to the SERP and how quickly; how long a user hovers over SERP results; and the user’s scrolling patterns on the SERP. From such data, a GSE learns not only about the user’s interests but also the relevance of the search results and quality of the webpages that the user visits.

Again, Google’s prodigious scale is a tremendous advantage, and some of the numbers from the court document are staggering:

Google gets 19 times more US mobile searches than all competitors put together.

Google’s Navboost trains on 13 months of data, but it would take Bing 17.5 years to gather this much data.

98.4% of unique long tail search phrases are only seen by Google.

The court document explains how Google uses all this information to improve search quality and advertising:

Armed with its scale advantage, Google continues to use that data to improve search quality. Google deploys user data to, among other things, crawl additional websites, expand the index, re-rank the SERP, and improve the “freshness” of results (i.e., bring them up to date). Click-and-query data also is used to build and train models that algorithmically improve results’ relevance and ranking, as well as to run large-format experiments to develop new features. Scale also improves search ads monetization.

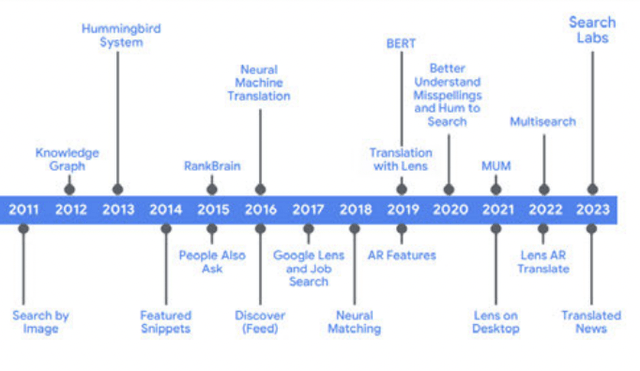

Citing a Microsoft document, the court document explains Google’s network effects:

1. More user data brings about improved search quality.

2. Better search quality brings more users and improves monetization.

3. The users/monetization attracts more advertisers.

4. More advertisers mean higher ad revenue.

5. Higher ad revenue allows investments such as revenue share agreements, which keep the cycle going.

Here is a Microsoft illustration in the court document:

Google Network Effects (Memorandum Opinion court document)

AI And User Intent

Google has been using artificial intelligence for years, but this was overshadowed when ChatGPT became popular. At that time, people were especially worried about Google with concerns such as the following:

1. People might not use traditional search engines like Google as much in the future.

2. New search engine competitors can come in and replace Google’s traditional memorization systems like Navboost and QBST with AI systems, eroding some of Google’s competitive advantages.

It hurts Google indirectly when they lose noncommercial queries because it takes away user data they would otherwise collect. Having said that, losing commercial queries is much worse and the court document reminds us that there is a distinction:

A noncommercial query is one in which the user seeks to retrieve information that the GSE does not attempt to monetize by delivering a search advertisement. 80% of Google’s queries are noncommercial in nature.

Regarding concern #1 above, Google’s search revenue is still very strong, and it doesn’t look like their traditional search engine is being displaced anytime soon, at least with respect to commercial queries. When ChatGPT became popular, many conjectured that people would stop doing commercial searches on Google and switch to ChatGPT for answers instead. One of the reasons this hasn’t happened in large volume is because user intent is often to bring about search engine result pages (“SERPs”) with different views, as opposed to having an answer in paragraph form. In this way, users can decide which responses resonate and make follow-up queries accordingly. In other words, we might initially think our intent is to answer a simple question, but the true goal can be more involved, and we often need resources with different viewpoints for circling back.

This kind of brings us to concern #2 above. Google could be in danger if apps like ChatGPT could morph and offer a SERP type option for users instead of just posting answers in paragraph form, such that they become kind of like a search engine instead of just a chatbot. This doesn’t seem to be happening any time soon either, and we can look at the court document for a better understanding.

Latency is the delay before a transfer of data begins following an instruction for its transfer. This was discussed in the October 2023 testimony with Google Search VP Pandurang Nayak. There have been times when Bing has been better than Google with respect to latency, and I’m conjecturing that much of this is because Bing is culling through less information and giving less accurate and less thorough answers. Nonetheless, Google wants to keep latency low, and this can be difficult when recent LLM signals like MUM are asked to do too much. I believe latency is one reason why LLM signals like MUM have not replaced traditional data-based memorization signals like Navboost and QBST in ranking. The court document talks about this (emphasis added):

The more recent LLM signals did not replace Navboost and QBST in ranking. (“Navboost remains one of the most [powerful] ranking components historically[.]”). Nor did they render the generalization systems obsolete. LLMs are used as “additional signals that get balanced both against each other as well as against other signals[.]”

Per the court document, Google’s former Software Engineer Eric Lehman said deep learning systems are much harder to understand than traditional memory systems based on user data (emphasis added):

Importantly, generative AI has not (or at least, not yet) eliminated or materially reduced the need for user data to deliver quality search results. (“[T]he middle problem of figuring out what are the most relevant pages for a given query in a given context still benefits enormously from query click information. And it’s absolutely not the case that AI models eliminate that need or supplant that need.”); ( MUM “definitely” did not replace traditional data-based signals, like Navboost and QBST).

Regarding #2 above, Neeva gives us insight. While defending themselves, Google points out Neeva and DDG as two market entrants during the timeframe which was allegedly a monopoly period. Google says Neeva failed because of their subscription model, but the court says parts of Neeva’s failure was because AI can’t yet replace traditional building blocks, including memory-based systems like Navboost and QBST:

Currently, AI cannot replace the fundamental building blocks of search, including web crawling, indexing, and ranking. Neeva’s experience is again illustrative. Despite building a search engine enhanced by AI technology, Neeva could not ride it to market success. AI may someday fundamentally alter search, but not anytime soon.

Best Search Engine By Far

One of the reasons Google has a nice business is because they have the best search engine. The development, planning, innovation investments, utilization of scale and utilization of AI factors above are some of the reasons for this. Throughout the industry, it is widely recognized that Google is the best by far.

The reality of the competitive landscape is simpler than one may think. The court document quotes Apple Services Senior VP Eddy Cue saying Bing is an inferior search engine. And per the court document, both Yahoo and DuckDuckGo use Microsoft’s/Bing’s search results. Even on Bing, “google.com” is the number one search.

The court document quotes Apple saying the following (emphasis added):

Google still has the best search engine by far.

Per the court document, Mozilla sees Google as a winner (emphasis added):

Google is the clear winner when it comes to product experience and what users want.

The court document mentions T-Mobile’s (TMUS) praise saying Google (emphasis added):

provides customers with the best overall device experience.

Summing up Google’s envious position, the court document says the following (emphasis added):

It has long been the best search engine, particularly on mobile devices. Nor has Google sat still; it has continued to innovate in search. Google’s partners value its quality, and they continue to select Google as the default because its search engine provides the best bet for monetizing queries. Apple and Mozilla occasionally assess Google’s search quality relative to its rivals and find Google’s to be superior.

Given Google’s superior search engine and excellent advertising system, companies like Apple are highly incentivized to make revenue sharing agreements with them as the default search engine. Apple’s rev share percentage today is supposed to be confidential, but a November 2023 Bloomberg article revealed it is 36%. At the time of an analysis in the court document, Apple’s rev share was about a third of revenue, or 33.75%. The court document explains how Microsoft was unsuccessful in terms of reaching a deal with Apple to replace Google with Bing (emphasis added):

Microsoft understood that it “would have to pay and even subsidize the transfer” for the period of transition and was willing to do so for the long term. Microsoft offered Apple a revenue share rate of 90%, or a little under $20 billion over five years. It did so recognizing that “there was going to be a period of turbulence of shift,” both as a result of the change and assuming that Google would respond by encouraging users to abandon Safari for its browser, Chrome. When that offer was not accepted, Microsoft proposed sharing 100% of its Bing revenue with Apple to secure the default or even selling Bing to Apple.

Per the court document, Apple knew 100% of Bing revenue would be much worse than a third of Google’s revenue:

Apple was concerned that despite the high revenue share percentage, Bing would not be able to bring in sufficient revenues because it was “horrible at monetizing advertising.” (“If you have an inferior search engine, customers wouldn’t use it, and so, therefore, I don’t know how you could monetize it well.”).

Apple Services Senior VP Cue says it was a no-brainer to stay with Google (emphasis added)

Otherwise it [was a] no brainer to stay with Google as it is as close to a sure thing as can be. (And so Google’s a sure thing. They have the best search engine, they know how to advertise, and they’re monetizing really well.).

The court document goes on to highlight Apple Services Senior VP Cue saying there was no price Microsoft/Bing could offer in order to give Apple a better deal than the one they had with Google:

According to Cue, there was “no price that Microsoft could ever offer [Apple]” to make the switch, because of Bing’s inferior quality and the associated business risk of making a change. (“I don’t believe there’s a price in the world that Microsoft could offer us. They offered to give us Bing for free. They could give us the whole company.”).

Per the court document, Google themselves analyzed what Microsoft/Bing would need to offer Apple at the time in order to present a better deal. At that time, Microsoft would have needed to offer 122% rev share in order to compete with Google’s then deal, which was about a third of revenue.

All of this means Google has a great business. Seeing as they have the best search engine and the best ad ecosystem, they only need to offer a fraction of their revenue for distribution agreements.

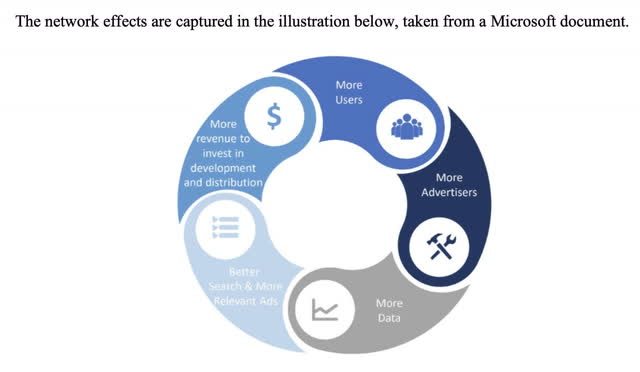

Given these considerations, it is logical to see today’s access points presented in the court document as being heavily skewed towards Google, the best search engine with the best advertising and the best monetization:

US search access points (Author’s spreadsheet based on the Memorandum Opinion court document)

Regulatory Risk

We have to understand the rulings against Google in the court document in order to measure regulatory risk. Many rulings in the court document went in favor of Google, but there were also serious rulings against them:

Ultimately, the court concludes that Google’s exclusive distribution agreements have contributed to Google’s maintenance of its monopoly power in two relevant markets: general search services and general search text advertising.

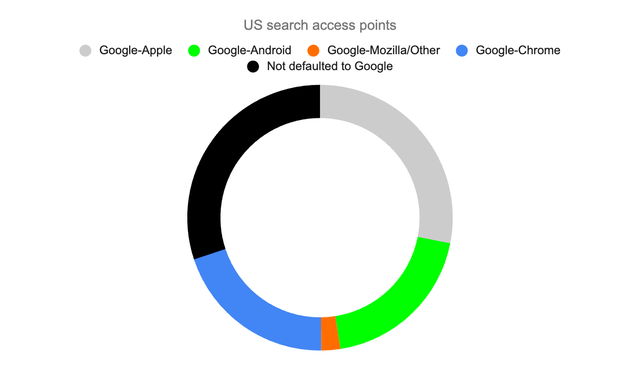

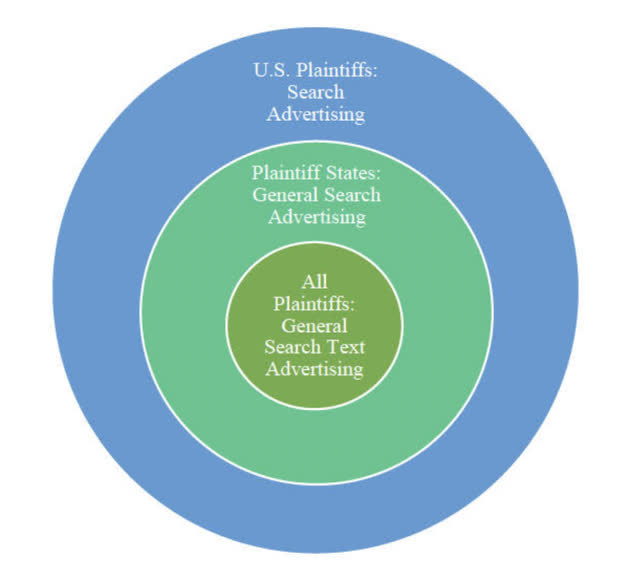

The court ruled that Google does not have a monopoly in the broadest search ad market nor the second broadest. However, the court did rule that Google has a monopoly in the most narrow of the 3 markets (emphasis added):

Plaintiffs collectively assert that Google has monopoly power in three overlapping advertising markets. These markets and their relationships are illustrated below. U.S. Plaintiffs allege the broadest proposed market, search advertising, which includes all advertisements served in response to a query, regardless of the digital platform. Within the search ads market, Plaintiff States define a general search advertising market that includes only ads served on GSEs. Finally, both sets of Plaintiffs propose a general search text advertising market, limited to text ads appearing on a GSE’s SERP.

Overlapping ad markets (Memorandum Opinion court document)

Here is how I think about the above ad markets:

Blue: Any search ads such as the text or PLA format from any digital platform such as Amazon (AMZN).

Green: Any search ads such as the text or PLA format but only on GSEs.

Olive: Only search ads in the text format and only on GSEs.

Again, the court ruled in favor of Google for the Blue and Green markets above, and we can conjecture as to some of the reasons for this. Google referenced Amazon when defending themselves, and the court document says the following:

Amazon’s US ads business is nearly the size of Google’s US retail ads business today, and is growing at over twice Google’s rate.

It’s hard to perceive how Google could have a monopoly in the Blue market above, seeing as Amazon is growing their ad business at over twice the rate of what we see from Google with respect to US retail ads. I believe this argument also helped Google defend themselves in the Green market, seeing as Amazon and Google compete for PLA advertisers.

As for the ruling against Google with respect to text ads, the court devotes extensive real estate in the document to exclusive dealing; this subject spans pages 214 to 258. Under this section, the court starts by reminding readers that rulings went for Google in the Blue and Green ad markets but against Google in the Olive ad market:

The court has found that Plaintiffs have proven that Google has monopoly power in two relevant product markets: general search services and general search text advertising. On the other hand, although the court recognized a separate market for search ads, it found that Google did not have monopoly power in that market. It also rejected a separate general search ads market.

The court says the bulk of the case is on distribution contracts (emphasis added):

The bulk of Plaintiffs’ case focuses on the search distribution contracts – the browser agreements (primarily with Apple and Mozilla) and the Android agreements (the MADAs and RSAs) – which Google allegedly uses to maintain its monopoly in the relevant markets.

The court says Google’s exclusive agreements preserve their monopoly:

The key question then is this: Do Google’s exclusive distribution contracts reasonably appear capable of significantly contributing to maintaining Google’s monopoly power in the general search services market? The answer is “yes.” Google’s distribution agreements are exclusionary contracts that violate Section 2 because they ensure that half of all GSE users in the United States will receive Google as the preloaded default on all Apple and Android devices, as well as cause additional anticompetitive harm. The agreements “clearly have a significant effect in preserving [Google’s] monopoly.”

We see 3 anticompetitive effects listed by the court with respect to the exclusive agreements:

The agreements have three primary anticompetitive effects: (1) market foreclosure, (2) preventing rivals from achieving scale, and (3) diminishing the incentives of rivals to invest and innovate in general search. Plaintiffs also contend that Google’s incentives to invest are diminished, but the evidence of that effect is weaker than the others.

The exclusive distribution agreements are repeated many times in the court document (emphasis added):

Google has not met its burden to establish that valid procompetitive benefits explain the need for exclusive default distribution. Accordingly, Plaintiffs have established that Google is liable under Section 2 of the Sherman Act for unlawfully maintaining its monopoly in the market for general search services through its exclusive distribution agreements with browser developers and Android OEMs and carriers.

Obviously, if Google is successful with their appeal, then regulatory risk fades.

If Google is unsuccessful with their appeal, then there is a wide range of possible outcomes. As we said earlier, in 2020, [general search] text ads made up about 80% of Google’s search ads by revenue. Given the way the court emphasizes exclusive distribution agreements, Google could see substantial changes with respect to future agreements with Apple and Android. One extreme scenario is a partial breakup with a forced divestiture of Android. An August 13th Bloomberg article also mentions a possible divestiture of Chrome, but I felt the court placed more of an emphasis on Android than Chrome. Citing DuckDuckGo, an August 13th NY Times article talks about potential regulatory outcomes (emphasis added):

The company said that the government should ban the agreements that made Google’s search engine the default option on devices, give others access to Google’s search and ads knowledge, present screens that allow people to change search engines easily and educate the public about the process of picking a new search engine.

I don’t know what future agreements will look like with Apple. The court document showed it is possible to split the default search engine, seeing as Mozilla did this from 2021 to 2022 when they switched from Google to Bing for 0.5% of desktop Firefox users.

Google’s relationship with advertisers is subject to change. As a result of this court ruling, Google might be banned from using pricing knobs such as squashing in the future. Additionally, Google might be forced to go back to allowing advertisers to opt out of keyword matching.

Valuation

My valuation thoughts haven’t changed much since my July article, but I am a bit more conservative at this point, and I now see the stock as a hold. Since the time of my July article, this court document has demonstrated that their business is even better than I thought. However, the ruling against Google with respect to text ads is serious. If Google loses their appeal and the regulatory consequences turn out to be severe, then their business may end up being worse than how we thought it was in July.

Disclaimer: Any material in this article should not be relied on as a formal investment recommendation. Never buy a stock without doing your own thorough research.