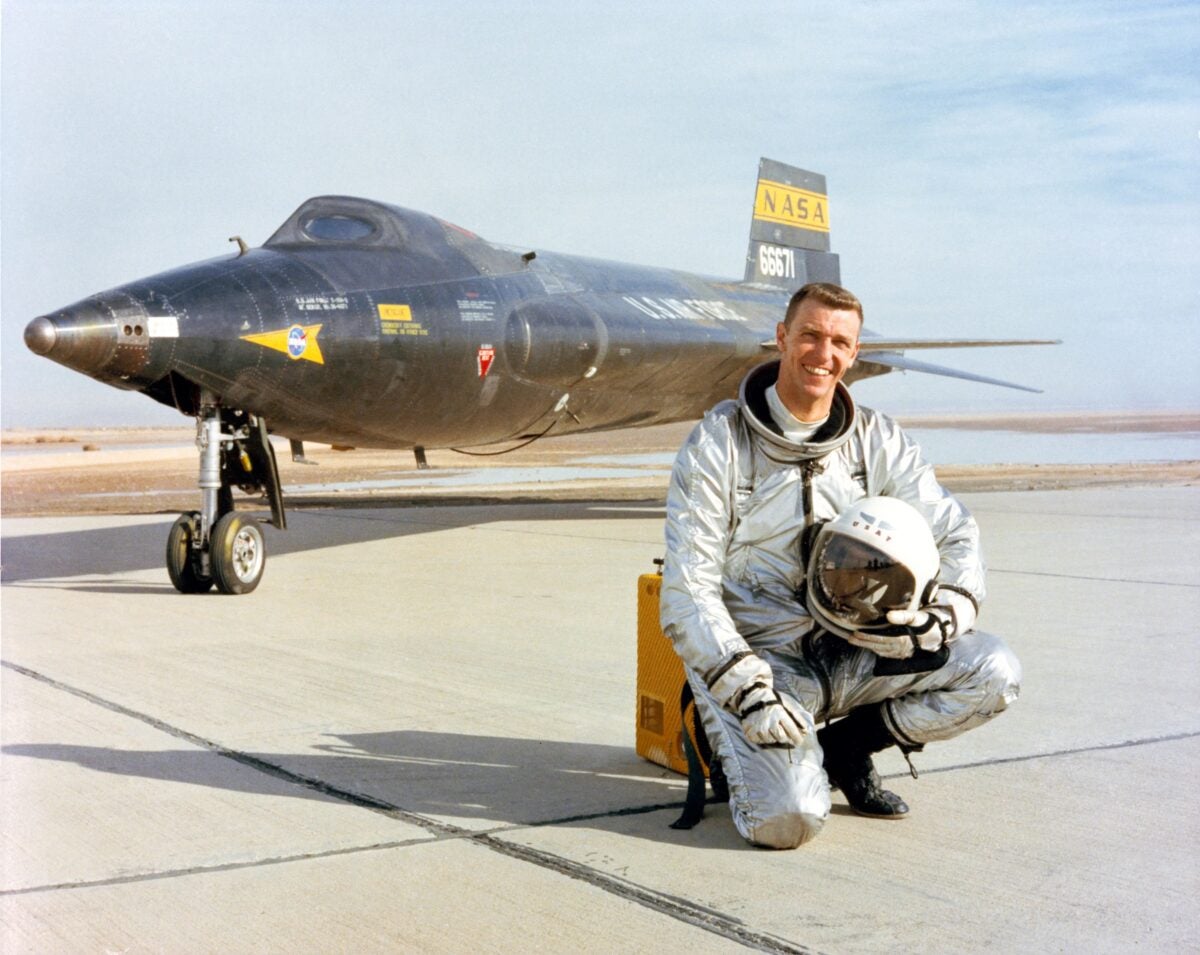

NASA astronaut Joe Engle wearing flight suit in front of an X-15 fighter in 1963. Credit: NASA

Astronaut, adventurer and aviator extraordinaire Joe Henry Engle, who passed away on June 10 at 91, earned renown in his career as the first human to reach space three times. He was also the only person to manually fly a Space Shuttle mission through almost its entire reentry.

Engle was a retired Air Force general, with a penchant for American-flag ties and polished cowboy boots, that piloted 185 aircrafts, logged 15,400 hours of flight time and was the first person to fly to space in two different winged vehicles: the Shuttle and the X-15. He is one of few U.S. astronauts who commanded a crew on his first orbital mission.

Born on August 26, 1932 in the farming community of Chapman, in central Kansas, Engle was the son of a high school agriculture instructor father and teacher mother. Neither parent was an aviator, but regardless, Engle grew up with an urge to fly.

“My mom used to say…that she couldn’t remember me seriously wanting to do anything but fly airplanes,” he told NASA’s Oral History Project in 2004. “Of course, I went through the fireman and cowboy games, but my core desires and core toys were always airplanes and flying.” His sister even cut a toy airplane from an old fruit can, but the tin was sharp-edged, resulting in his mother forbidding him from playing with it.

He read airplane magazines, watched airplane movies at Chapman’s only cinema, then went home to dig a cockpit in the sand. “I would get a tree branch for the control stick,” Engle remembered, “and take old tin cans and push them in the front for instruments and just be a hero, shoot down Japanese Zeroes right and left.”

Chapman had no runway, but at one Labor Day event Engle watched an old Stearman biplane alight in a nearby alfalfa field. He bought a ride. “We went around town once in it and back and landed,” Engle said, “and that was my first exposure to flying.”

It was an exposure that lasted a lifetime. He soon entered the University of Kansas to pursue aeronautical engineering, earning his degree in 1955. Engle worked summers as a draftsman for Cessna Aircraft. His supervisor Henry Dittmer got him sweeping hangar floors in exchange for flying lessons in a two-seat Cessna 120 taildragger.

Engle entered the Air Force via the Reserve Officers Training Corps and after flight instruction, he completed gunnery school. He then trained as a fighter pilot at George Air Force Base. He flew the F-100 Super Sabre in air-to-air combat and dogfighting over California’s Death Valley and Stovepipe Wells. It was the Air Force’s first level-flight supersonic fighter—and the hottest jet in the sky.

In 1960, Engle was picked for the Aerospace Research Pilot School, graduating a year later and moving into flight test at Edwards Air Force Base. “It was like getting a master’s degree,” he said. “Very intense, academically and flying-wise.”

Hopes of joining NASA in 1963 went nowhere, for General Irving ‘Twig’ Branch of the Air Force Flight Test Center had other plans for Engle. That June, he joined a hotshot team of pilots flying the X-15 rocket-propelled aircraft to the edge of space.

“That just thrilled me to death, because it was a chance to get into space and to do it with a winged airplane, with a stick and rudder,” said Engle. Flying the X-15 was not something anyone applied for: it was a gift. “You just kinda sat back,” he added, “and hoped that somehow the gods would sprinkle that dookie dust on you that had X-15 on it.”

Awaiting his first flight, Engle rode his little Lambretta motor scooter daily across California’s back desert roads to simulator sessions. He flew the X-15 sixteen times over two years, including three missions in June, August and October of 1965 when the aircraft’s throttleable rocket engine—capable of 26,000 pounds (12,000 kilograms) of thrust—pushed him above an altitude of 50 miles (80 kilometers).

And since the Air Force accepted that as space’s lower limit, it awarded ‘astronaut wings’ to X-15 pilots who conquered it. “You could make sure you got into space by letting the engine run another second or two,” Engle said. “By the time the ground could see it on radar, it was too late to do anything about it.”

Engle became the first human to enter space (but not Earth orbit) on three occasions. The first and highest of these flights was achieved on June 29, 1965 by attaining a peak altitude of 280,600 feet—equivalent to 53.14 miles (85.5 kilometers). Proudly watching at Edwards base were his parents.

But keenly aware that military assignments were never open-ended, Engle reapplied for NASA and was picked as an astronaut in April 1966. It brought mixed emotions, leaving the best flying job in the world for a chance to travel to the Moon.

In August 1969, he was named backup Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) on Apollo 14, planned for January 1971. But when performance issues arose with the prime LMP, consideration was briefly given to giving the position to Engle. However, Engle was less knowledgeable on the LM’s quirky systems and the prime LMP kept his seat on the mission.

It was a decision that Apollo 14 backup commander Gene Cernan came to regret.

Under NASA’s astronaut rotation policy, backups for a given mission tended to rotate into the prime crew slot three flights later, allowing Cernan, Engle and Command Module Pilot (CMP) Ron Evans to confidently consider Apollo 17 as theirs to fly. But when Apollo 18, 19 and 20 were scratched by budget cuts, the scientific community anxiously pressed for a geologist aboard Apollo 17.

NASA had just one geologist-astronaut, Jack Schmitt, and he was pointed at Apollo 18. With Apollo 18 now gone, in August 1971 NASA bowed to scientific pressure and put Cernan and Evans on Apollo 17 but deleted Engle in favor of Schmitt. Engle later said his toughest job was telling his children he would not be going to the Moon.

Yet he handled himself with gracious dignity. “You can do one of two things,” he told the Houston Post. “You can lay on the bed and cry about it, or you can get behind the mission and make it the best in the world.”

That attitude earned him great respect as he began working on the Shuttle. In late 1977, he and Dick Truly flew Shuttle Enterprise twice off the back of a Boeing 747 carrier aircraft and guided her to a smooth runway landing at Edwards base, part of a series of Approach and Landing Tests (ALTs) to evaluate the reusable spacecraft’s handling characteristics.

In November 1981, Engle and Truly flew Columbia on STS-2, the second Shuttle mission and the first-ever voyage of a reusable manned orbital spacecraft. A fuel cell failure cut their flight from five days to two, but the astronauts operated a package of Earth-viewing scientific instruments and tested the Shuttle’s Canadian-built robotic arm.

STS-2 returned home after 54 hours, Engle and Truly having worked through the night to get nearly 90 percent of their pre-flight tasks done. Homeward bound, they executed 29 maneuvers from Mach 24 to subsonic speeds, making Engle the only Shuttle commander to manually fly (almost) an entire reentry.

“We were very anxious to see how much margin the Shuttle in the way of stability and control authority, how much muscle the surfaces had at different Mach numbers and angles of attack,” he said. “Wind tunnels are very susceptible to a lot of variables, so you really want to know for sure what you have in the way of capabilities if you ever have to use them.”

In August 1985, he commanded STS-51I which launched three communications satellites and retrieved, repaired and deployed the crippled Syncom 4-3. Engle retired from NASA in November 1986, serving in several senior roles in the Kansas Air National Guard and was inducted into the National Astronaut Hall of Fame in 2001.

“I never met an airplane I didn’t like,” Engle said of his love affair with flight. “Some are less relaxing and less enjoyable and less fun to fly and some of them are a lot more work to fly than others. But they’ve got their own personality.”