Hot on the heels of its successful mid-air booster catch during its Sunday Starship Flight 5 mission, SpaceX is preparing to launch a Falcon Heavy rocket from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center around lunchtime on Monday.

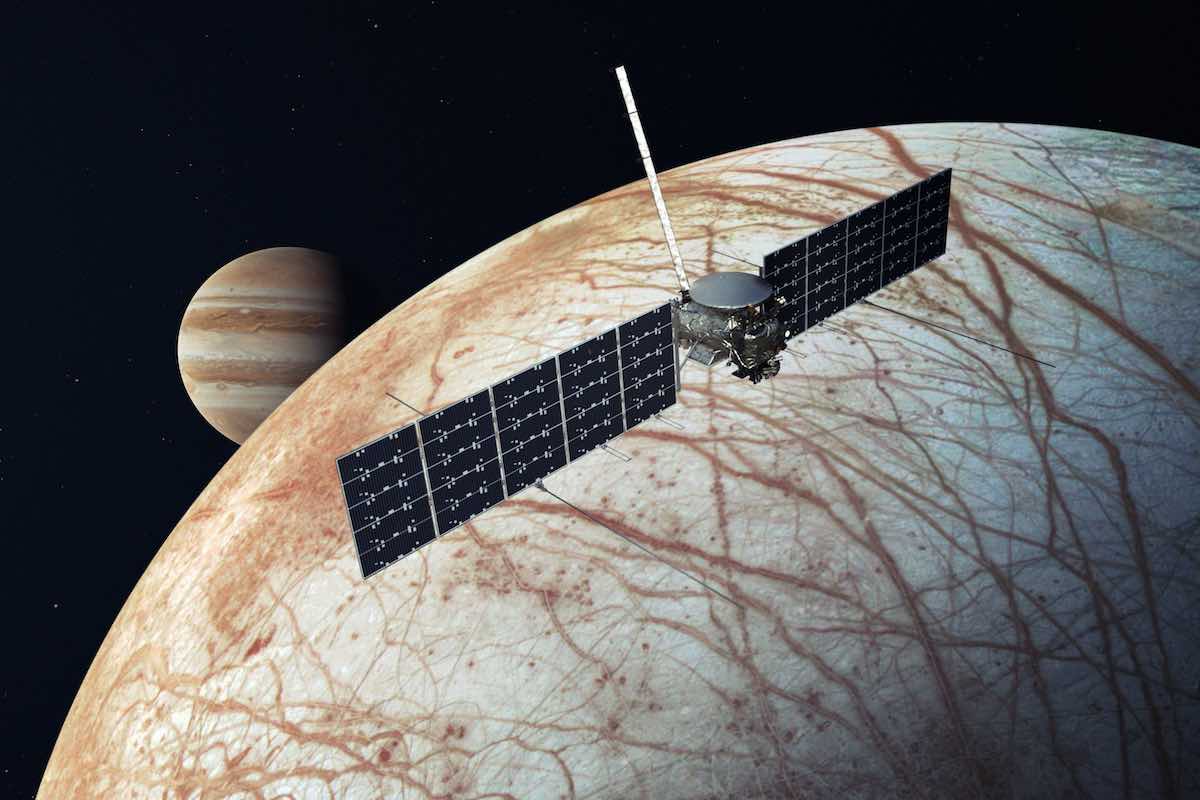

Onboard the three-core vehicle is NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft, which will embark on a year’s long expedition to Jupiter’s ocean moon, Europa. NASA believes this moon, characterized by its icy exterior and the ocean beneath it, may contain evidence suggesting that the building blocks for life might exist on another celestial body besides Earth.

Europa Clipper will be sent on an Earth escape trajectory to begin a nearly six-year mission to its namesake moon. Liftoff of the mission from Launch Complex 39A is set for 12:06 p.m. EDT (1606 UTC). The launch time can move earlier by up to 15 seconds if needed to avoid any potential collisions wiht objects in orbit.

Spaceflight Now will have live coverage beginning about an hour and 15 minutes prior to liftoff.

This Falcon Heavy mission is a unique circumstance that will require SpaceX to expend all three of the rocket’s boosters. In most Falcon Heavy flights, the two side boosters are flown back to Cape Canaveral Space Force Station after separating from the center booster, which is not recovered.

“Falcon Heavy is giving Europa Clipper its all, sending this spacecraft to the furthest destination we’ve ever sent, which means the mission requires the maximum performance,” said Julianna Scheiman, Director of NASA Science Missions for SpaceX, during a prelaunch media teleconference.

“I don’t know about you guys, but I can’t think of a better mission to sacrifice boosters for where we might have an opportunity to discover life in our own solar system.”

The mission is the sixth and final flight for side booster, 1064 and 1065, will make their sixth and final launch. They both previously supported the launches of USSF-44, USSF-67, Jupiter-3/EchoStar-24, NASA’s Psyche and USSF-52.

Following the impacts of Hurricane Milton, the mission was originally scheduled for Oct. 13, but NASA and SpaceX decided to delay 24 hours. During the teleconference, Scheiman said that was due to an issue that came up during a prelaunch mission assessment SpoaceX calls a “paranoia scrub.”

“During that process, we encountered a quality control issue related to our vehicle tubing. And there’s tubing on all over in different parts of the rocket. So one of the things we have done, working really closely with our NASA Launch Services Program team, is looked at what, what hardware on the vehicle was set, was suspect, was needed to be evaluated as part of this issue, and make sure that it had its necessary checks and validation as needed,” Scheiman said.

“So basically making sure that every system went through an acceptance test or a validation test or an additional type of inspection to make sure that the vehicle and the hardware that’s on the pad vertical right now is ready to fly.”

Tim Dunn, the senior launch director for NASA’s Launch Services Program (LSP), added that SpaceX brought up the issue late last week and NASA agreed that the issue needed further work.

“Our teams worked hand in hand for most all of Friday evening and all day [Saturday], to get to a very confident risk posture today (Sunday) as we went into our launch readiness reviews,” Dunn said. “So we’re in very good shape, and we do appreciate SpaceX’s paranoia.”

While the mission doesn’t involve the Federal Aviation Administration’s commercial launch licensing process, since it’s a NASA-led mission, the issue of the Falcon 9 upper stage anomaly that cropped up during the Crew-9 mission did come up during the prelaunch briefing.

Scheiman said the Merlin vacuum engine on the second stage of the rocket, which is the same used on a Falcon Heavy, burned for 500 milliseconds after the shutdown command was issued for a deorbit burn.

“That half a second of extra thrust basically made it such that the second stage re entered the Earth’s atmosphere slowly outside of the established zone for landing of that second stage in the South Pacific Ocean,” she said. “On our vehicle, everything responded as it was intended. We basically commanded a backup Merlin vacuum shutdown process that closed the open engine’s liquid oxygen bleed valve, that successfully shut down the MVac engine.”

NASA closely followed along with SpaceX’s analysis of the issue and said they were confident in the conclusions reached, but also did their own verifications to be extra sure.

“We partnered, obviously, with SpaceX because of the proximity of the Crew-9 mission to the Europa Clipper planetary window and SpaceX brought us quickly into that anomaly resolution,” Dunn said. “We held our own independent engineering review board just the day after our flight readiness review, where we assessed and cleared Europa Clipper of this anomaly.”

Exploring Europa

The journey to the icy moon of Europa is something that has been in discussion since the late 90s and was envisioned as a successor to the Galileo spacecraft, which orbited Jupiter from 1995 to 1997.

The National Research Council recommended a mission to Europa in 2013, which came with an estimated cost at the time of about $2 billion. By about 2019, mission cost estimates rose to around $4.25 billion and as of now, the mission has a total cost estimate of $5.2 billion.

Fully fueled, the spacecraft clocks in at about 5,700 kg (~12566 lbs.) and is powered by 28 thrusters. For a sense of scale, with its solar panels unfurled, it is longer than a standard basketball court.

Following spacecraft separation from the Falcon Heavy upper stage, Jordan Evans, the Europa Clipper project manager, said the team will first work to acquire the signal from the spacecraft, which will take a few minutes. That’s followed about two to three hours of Europa Clipper “rolling like a rotisserie to warm up [its] solar array mechanisms” and then it will use what Evans called “thermal knives” to cut the solar array restraints over the course of roughly 30 minutes.

“It takes about 30 minutes for the spacecraft to cut through all nine per side. So, it does eight per side and then at about 30 minutes after the initiation of solar array separation start, it cuts the ninth on either side,” Evans explained. “That occurs about three to three-and-a-half hours after launch and it will take a little while for us to identify the state of the vehicle following solar array separation.”

The journey to Europa will take five-and-a-half years, with Clipper set to arrive on April 11, 2030. The journey includes a Mars gravity assist on March 1, 2025, and Earth gravity assist in December 2026.

Sandra Connelly, deputy associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, said she is “super excited” for the mission, stating that it’s “a very important part of our [science] portfolio, as it will bring us one step closer to answering fundamental questions about our solar system and our place in it.”

“Scientists believe Europa has the suitable conditions below its icy surface to support life. Its conditions are water, energy, chemistry and stability,” Connelly said. “To do this, we will be collecting data from nine instruments and one science experiment. Science includes gathering measurements of the internal ocean; mapping the surface composition and geology; and hunting for plumes of water vapor that may be venting from the icy crust.”

While it’s at Jupiter, Europa Clipper will make about 50 flybys of Europa at its closest approach, which is about 25 km (16 mi) above its surface.